Τι μας αρέσει

Robin Hahnel Interview on Participatory Economics – Part 5 – Optimal Plan, Enterprise Incentives, Worker Control, Consumer Satisfaction

Editor’s Note: Discussion includes optimal and efficient production plans in Parecon, accounting of benefits and costs, enterprise incentives, worker control, and satisfying consumers.

[After The Oligarchy] Hello fellow democrats, futurists, and problem solvers, this is After The Oligarchy. Today I’m speaking with Professor Robin Hahnel.

Robin Hahnel is a professor of economics in the United States, and author of many books, but today I’m interviewing him as co-originator with Michael Albert of the post-capitalist model known as Participatory Economics (or Parecon).

Today’s conversation is in association with mέta: the Centre for Postcapitalist Civilisation. This is the third in a series of interviews with Professor Hahnel about participatory economics, and in particular his latest book Democratic Economic Planning published in 2021. If you haven’t watched the first two interviews check them out here.

It’s an advanced discussion of the model proposed in that book so I recommend that you familiarize yourself with participatory economics to understand what we’re talking about. You can do that by visiting participatoryeconomy.org. You can also read Of the People, By the People (2012) for a concise introduction to parecon. And Professor Hahnel has a new book coming out in a few months called A Participatory Economy (2022).

Robin Hahnel, thank you for joining me again.

[Robin Hahnel] Great to be with you again.

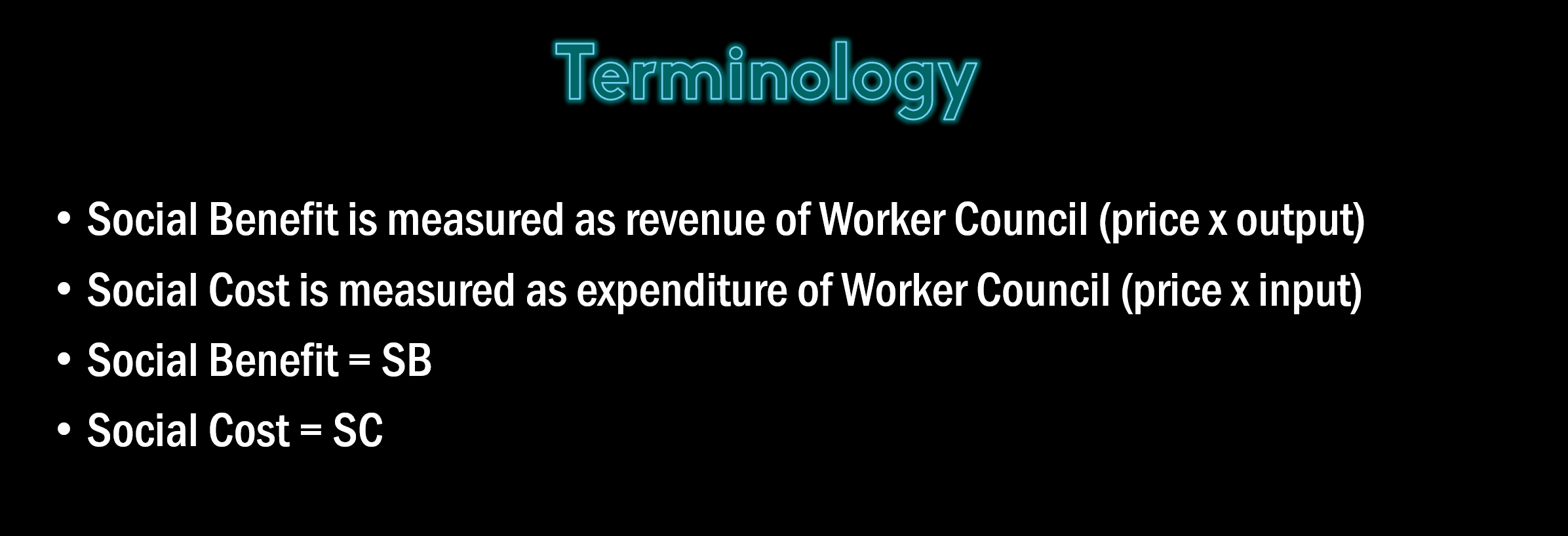

[ATO] Last time we were talking about production units and we’re going to continue talking about production units, as in worker councils, as in enterprises. And the first question is a follow-up to part of our discussion last time, and we were talking about social costs and social benefits, and the incentives of worker councils in parecon.

So let me frame the matter by presenting my understanding of our last interview. This is going to be a bit technical for viewers but we will break it down and it will be understandable. So I asked you, essentially, ‘wouldn’t we want worker councils to strive for a social benefit much greater than a social cost rather than merely the social cost equalling the social benefit – or having a social benefit to cost ratio of one? Because that means producing the greatest net social benefit. And, if so, what will make worker councils do that?’

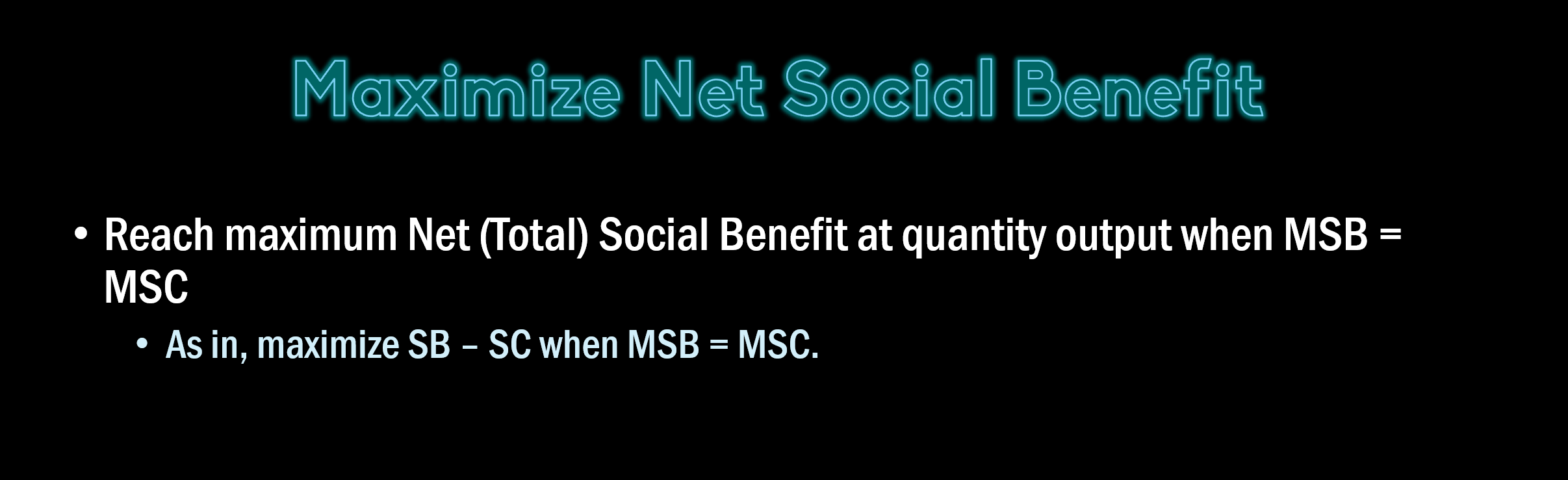

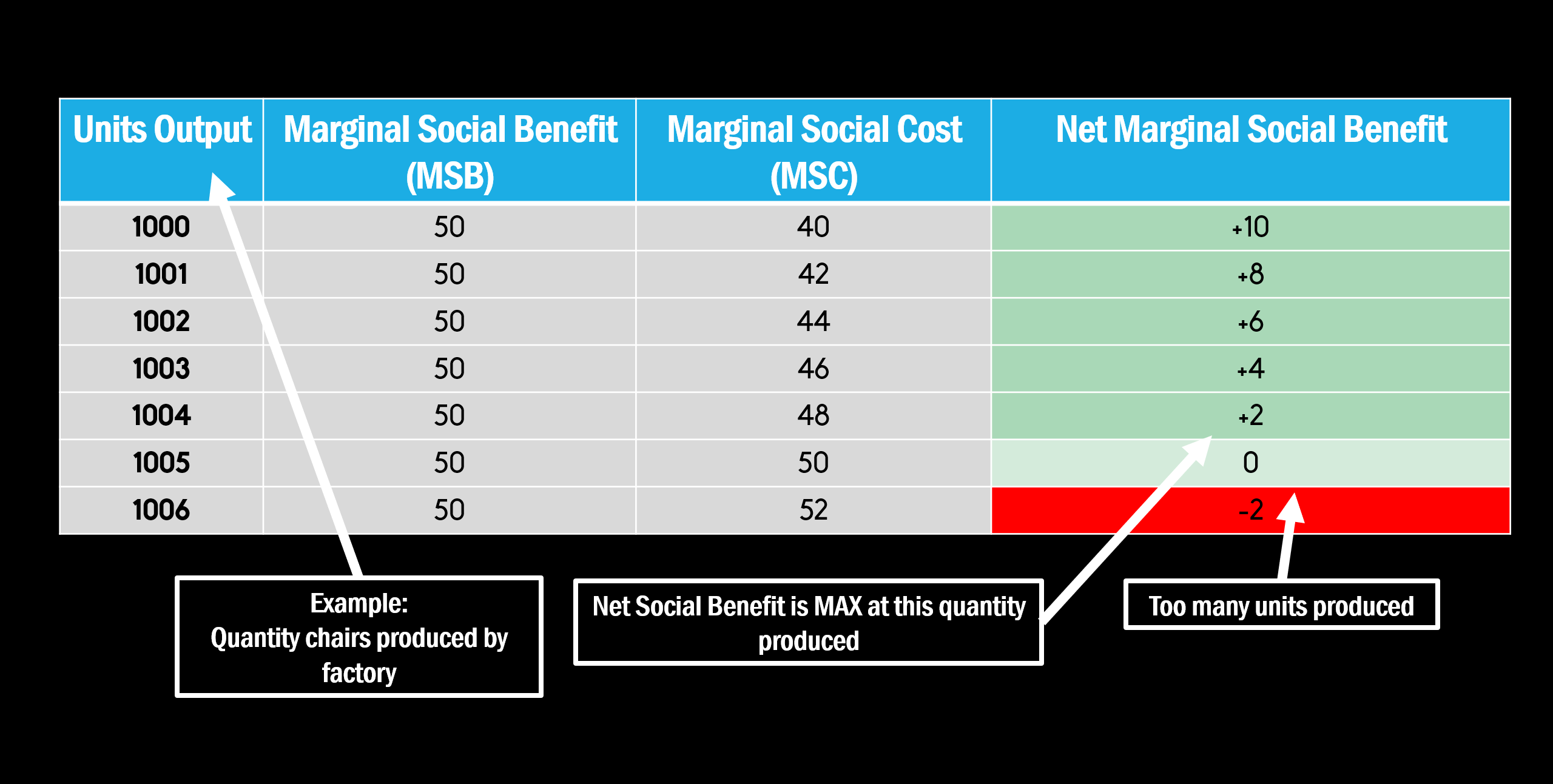

And you replied, basically, ‘no, we want worker councils to produce up until the marginal social benefit is equal to the marginal social cost. Because if the social benefit is greater than the social cost then there is still some net social benefit to squeeze out by producing another unit (like producing another chair). And this terminates when the marginal social benefit is equal to the marginal social cost, which is when the social benefit the social cost ratio equals one (SB/SC = 1).’

That’s a mouthful. So, this is my understanding of what was said at the time. Please correct me if I misinterpreted what you said during that interview because it seems to me that maybe there was a miscommunication. Because it seems to me that if you keep producing chairs up until the marginal social benefit of that chair is equal to the marginal social cost, that’s the point at which social benefits minus social costs is the greatest. But that’s not going to be the same as the social benefits divided by the social cost equal to one, that there is parity between social costs and social benefits. So could you just clarify or respond to that please?

[RH] First of all, I want to thank you for asking the question and probing on this. Because it is a little complicated and it forced me to go back and rethink through. So let me just see if I can lay it out there on in a straightforward way. What I’m going to lay out there is standard and then I’m going to explain why the way we model something is different from standard. And that’s I believe where the sort of miscommunication comes in.

So you’re absolutely right that the general efficiency criterion is you want total social benefits minus total social costs to be as large as possible. You want to maximize, as you’re saying, the difference between total social benefits and total social costs. I mean this principle is we call it the ‘efficiency criterion’ and applies to anything. Anything you’re doing, you want to do it so as to maximize the benefits to any and all people over all time periods minus the cost to any and all people of overall time periods.

Now, mathematically what that is equivalent to is you want to keep doing something up to the point where the last little unit of whatever you did generated exactly the same amount of social benefits as it did increase social costs. So saying you want to maximize the difference between total social benefits and total social costs is the same as saying you want to keep doing something up to the point where the marginal social benefit of the last little bit of it you did is exactly as big as the marginal social cost of the last little bit you did. That’s just mathematics.

Here’s where things get a little complicated. When we’re talking about social benefits, then the context in which I’m always talking about it is I’m thinking of a particular worker council or a particular consumer council. Then you have to ask well the social benefits in the mathematical pure sense includes everybody, which means it includes the council that we’re considering. So social benefits are usually thought of as being social benefits for others, for everybody else other than the worker council; and social costs are usually thought of as being only the social cost to those who aren’t in the council.

I mean one thing that’s always a little bit delicate or complicating is these social costs that we’re thinking of cost a society something that a worker council does. That includes the opportunity cost – traditionally, as everybody does it – of using scarce labour in that worker council. If you have you have a certain amount of engineers and carpenters in an economy, any time one worker council uses them they can’t be used in another worker council. And that we traditionally call an ‘opportunity cost’. So standard treatments will include the opportunity cost of using engineers or carpenters in any workplace, in any worker council. It doesn’t usually include something that mainstream economists call the ‘disutility of labour’. So there’s a scarcity cost to using labour but in addition – for labour, unlike other inputs – there’s also not just an opportunity cost, performing the activity might be more or less pleasurable, or more or less unpleasurable.

Usually, traditionally, when we’re talking about social costs for a workplace we include the opportunity costs of using these different categories of labour but we don’t really include the disutility. Or at least it’s possible not to include that part. Now, for two particular reasons, that I’m going to come to in a minute, we chose to model worker council and consumer councils in a particular way.

For consumer councils it’s very straightforward and easy to understand. A consumer council should maximize what economists call their utility, their well-being, their satisfaction from the activities they engage in. And for a consumer council we usually think of the activities of people are engaging in as what are called consumption activities. So the whole idea is you want your consumer council to maximize the well-being they get out of their consumption activities. Oh, but it’s subject to a constraint. And I’m going to use this phrase to describe the constraint: broadly speaking I would say as long as what they’re consuming is socially responsible. And in the case of a consumer council what social responsibility amounts to is well it would be irresponsible if the social cost to society of their consumption activity was larger than what we consider to be their fair income. So for a consumer council we basically have this set up where what we want them to do is to maximize their well-being as long as they’re being socially responsible. As long as the social cost of society of their consumption activity is what I would call justified or warranted by the income that they fairly have. And for us that income for some of them it’s their income from work, and for some of them it’s their social security payment or their childcare allowance or whatever it is.

We wanted to model worker councils exactly in the same way. We wanted to say, hey, these are people, these are humans engaged in a human activity. It happens to be an activity we think of as work or production rather than consumption. But the worker council is a bunch of people engaged in an activity and we want them to maximize the satisfaction or utility they get from engaging in their activity as long as their activity is socially responsible. So, we modelled worker councils as maximizing … Now, in their case it may be maximizing the satisfaction you get from the work process that you engage in. What it may amount to is minimizing the disutility of your labour. But still, it’s the same sort of … I mean where we had reasons, basically underlying methodological reasons, for wanting to view the entire thing in this way, sort of very symmetrical to what it is that consumers are doing.

So for a worker council what we said is we’re going to assume that what they’re going to try to do is to maximize their utility subject to the social responsibility constraint. Now, for us the social responsibility constraint is: nobody should object to them doing what they want to do as long as what they’re doing is not making anybody else worse off. So we model their social responsibility constraint as: worker council do whatever you want, as long as the social benefits – and now these would be the social benefits to any and all other people – are at least as great as the social cost to any and all other people. And that’s the way we set up our procedure. That’s the way we set up our model.

And when we say that the annual participatory planning procedure will achieve an efficient outcome, or in economist language a Pareto optimal outcome under certain assumptions, what we mean is if worker councils do this and if consumer councils do this, we can prove that the outcome will be socially efficient. It will be a Pareto optimum. Now you might ask well why did we want to model things this way? And this is where I thank you for forcing me to think back why decades ago we did this.

It was for two reasons. We actually believe in self-management. I think there’s long been a divide between anti-capitalists, between the anarchists and the socialists, or on the question of socialism how libertarian a socialist are you. And I think we’re firmly in the camp of feeling that there is a very important, great, value put on doing things in a way that provides workers and consumers with self-management. So if you’re thinking in terms of self-management, then the idea that we want people, we want workers and consumers to be doing whatever they want as long, as they’re behaving in socially responsible ways is in our mind the right way to look at it.

And the other thing is – I now recall when I was thinking back over it – we felt like there was an advantage to reminding people that basically any and all human activity is similar in a certain kind of way. That any and all human activity basically has the same purpose which is maximizing human well-being, whether it’s work activity or its consumption activity. What we’re trying to do, or what we think as libertarian socialists we should be trying to do, is to maximize human well-being, but we want to leave that to the people whose well-being it is to decide what gives them well-being and what does not. So we want them to self-manage their own search for well-being, provided that it’s being done in socially responsible ways.

When I thought back over it I thought well Robin why did you set up the process and the formal treatments in a way that, quite frankly, is not common, that is not the standard way in which it’s done? And that’s why I was thanking you for reminding me of that, because now I remember that’s why we did it this way. And actually I was happy to discover that I think I am as comfortable, if not more comfortable, now as when we made those decisions back decades away ago about, well, why don’t we analyse it this way.

You’re correct that the constraint for the worker council just says you’re not making anybody else any worse off than they would have been had you not done what you just said you wanted to do. And that’s different from maximizing for any and all people the difference between total social benefits and total social costs. But in a sense what we’re saying is we’re actually concentrating on a part of benefits or cost that doesn’t really usually get considered when people talk about social benefits and social costs. And that’s the actual well-being and the size of the actual well-being or the quantification of well-being or utility of the workers in the workplace where whatever is going on is going on.

So that’s my very long answer to what I think was a very perceptive and probing question on your part.

[After ATO returns from dealing with food poisoning]

Nobody’s going to believe that that you’re not vomiting today because you were overly excessive in St. Patrick’s day yesterday. I mean it’s there’s just no credibility there whatsoever.

[ATO] I know, and the funny thing is you know I’m the one Irishman who basically doesn’t drink. I mean, I drink sometimes but …

[RH] No, I know when you told me … I mean, I didn’t tell you how disgusted I was when you said you drank non-alcoholic beer that’s just an abomination in my book.

[ATO] Well look, when I’m at home I just prefer to drink non-alcoholic beer.

I actually feel much better now, alive, and I can think and everything, which is good because this is probably the most complex topic that we’ve talked about. And I’m sitting there thinking ‘don’t get sick’.

So, let me let me respond to what you said and then I’ll pose some questions. Thank you very much for that explanation, for clarifying that, and I think saying it in an understandable way. It’s very interesting, what you were saying. And I think that this has very deep significance for an economy, for participatory economics.

There are a few things that occur to me. I’ll start with the one that’s most obvious to me. One might immediately hear this and say ‘yes, worker self-management is very important. Maximizing – if we want to put it this way – the utility of workers in the production process or minimizing disutility, this is very important, and this is something that should be done.’ But one might say that imposing the constraint that the worker council must be socially responsible as meaning social benefits must be at least equal to social costs – breaking even, basically – it might be necessary, it might be the minimum, but it might not be sufficient or desirable in terms of how we want an economy to function. In the sense that if everybody’s breaking even all the time, assuming that that was the case, would we not want there to be a more efficient use of resources?

You understand what I’m getting at, so how would you respond to that?

[RH] You may be right. And you forced me to think about some things that I had not necessarily thought about before. If you’re an academic and you’ve published something, and somebody comes up with something, the first instinct is oh my god, I need to go and check and make sure that what was actually published is still correct, or else if I’m an honourable person I’d have to issue a retraction. And so I skedaddled over to make sure that my proof that the planning procedure was pareto optimal still held, and I let out a huge sigh of relief when I discovered no, no, what we’re talking about now does not negate the proof that the planning procedure will be pareto optimal under the setup of the model.

But I would say yes, thinking out loud about it could be that the constraint should just be that the marginal social benefits have to be equal to the marginal social cost. That that’s the constraint under which the worker council is trying to maximize their satisfaction and their pleasure from work. And I suspect it would work out very much this the same.

The other thing is this particular issue had come up as a somewhat divisive issue amongst all of us who in some way or another support the model. but in a different way and for a different reason. The discussion there had to do with what should the average effort rating be for workers in a council. Figuring out within a council – and I think you have some questions on this subject coming up anyway – but within a council you know it’s very clear-cut what we’re proposing and what we have suggested would be a reasonable way of trying to decide if there’s any differences in the efforts and sacrifices that that workers within a worker council are making.

But we have conceded the get-go there needs to be a cap on average effort ratings for every worker council. Or else there’s going to be a tendency for every worker council to say why should I be judging my work mates harshly? It’s just easier for me if we can all award each other very high effort ratings and then we’ll all have very high consumption allowances. So there’s that perverse incentive, and you eliminate that perverse incentive completely if you cap the average effort rating in every council.

But that doesn’t tell you what the cap has to be. Any cap will accomplish that goal. And the question then is well for two worker councils who have the same social benefit to social cost ratio it would seem clear they should have the same cap. And we don’t want any worker council proposal to be accepted if the social costs are actually higher than the social benefit. But that leaves open the possibility that we’d have some worker councils where the social benefit the social cost ratio is exactly one, and then maybe some other worker councils where the social benefit the social cost ratio is 1.05.

And so the debate, that’s sort of an unsettled debate amongst advocates for a participatory economy model, is well should the average effort rating of that second worker council be five percent higher than the average effort rating for the first worker council? And, in theory, if the reason that the ratio is 1.05 in one of the worker council, if the reason for that is that the workers there are sacrificing more or just working harder, putting out more effort, then it would be a good idea. And some of us have said we should do that. On the other hand, there’s been debate and controversy over whether or not that would be a good idea.

One of the very important issues that would presumably influence your view on that subject is well just how accurate do you think our indicative prices are at measuring these opportunity costs and the relative values of these different things? On the one hand, if you think this system is going to do a really good job of getting the indicative prices right, then you could make the case well the only reason that one worker council would have a higher ratio than another has to be because they were putting in extra efforts and then it’s warranted. On the other hand, if you think well these are good reasonable estimates, the indicative prices are the best we can do, but they’re not going to be that good, then there are some people who feel well the whole idea that you would propose that some worker councils have a higher average effort rating than others maybe isn’t such a good idea.

So, in that context there’s been a lot of discussion about this. And depending on which one of us you talk to, you get a slightly different view about where to come down on this issue. But you’ve raised this whole social benefit to social cost ratio as a constraint for a different reason, and basically I think of merit some thought

[ATO] They’re very closely connected. I mean, the topic that you raised there is directly connected. And it’s actually the second question. Reading through Democratic Economic Planning, I noticed that a number of times the fact that worker councils had an average effort rating cap proportional to the social benefit to social cost ratio – which you could take as one measure of economic efficiency, so that their average effort cap is tied to their production efficiency – seemed to actually be doing important work multiple times in the system. There might be a criticism or a concern that somebody might have and one of the replies might be well the fact that worker councils have their effort rating cap proportional to this SB/SC ratio will deal partially with that. And so, the second question there I was talking about is the ‘size six purple women’s high-heeled shoe with the yellow toe’ problem, which I think is a brilliant name.

[RH] Yeah, I think it’s a brilliant name too. But every time I talk about it, when I have to talk about it I can’t remember it. So I’ve created something that in writing I think is very felicitous but now I feel like I’m plagued by the fact that I’m going to embarrass myself because I can’t remember it. But anyway, go ahead.

[ATO] Yeah, it’s memorable but I can never remember it. It’s a bit like Chinese Whispers, every time another word is added on or deleted.

Anyway, the idea of that is it’s a question about basically why will a worker council produce exactly the kind of good to the level of specificity that consumers want. So, somebody doesn’t just want a shoe but they want a size six purple shoe which is a women’s shoe, a high-heeled shoe, and it’s got a yellow toe. That’s a wider discussion but part of the response to that on page 167 of Democratic Economic Planning is that there’s an incentive to produce the right shoe because otherwise the worker council would get a lower social benefit to social cost ratio.

Why would they get a lower ratio? It’s because less people would purchase the shoes that they produce and therefore their social benefit would be less. And therefore that SB/SC ratio would be lower. Just to explain to people. That’s obviously only true if that holds, if that effort cap is actually proportional to that SB/SC ratio.

[RH] No, that’s a good point.

[ATO] There are several other times where that occurs. It slips my mind now. So there’s an issue of fairness like you’re bringing up there about do the indicative prices capture all of the information that we want such that we can say a worker council’s effort rating will only be greater if the expenditure of sacrifice of the workers is actually greater. Okay, that’s one issue. But then there’s this other issue of overall though are we going to end up with a society that functions, according to other metrics, like we want. And I think those are important as well.

[RH] I do think that there is rather clearly an incentive for worker councils to produce the shoes that it turns out people want. And this is a legitimate issue. One of the criticisms of the centrally planned Soviet type economies was that there was just no incentive for the producers to actually produce the kind of products that people wanted. And so another way of putting it is socialists have to own up to that and people should scrutinize to see whether or not we have a more adequate response given the history.

And my point has simply been, look, I think it’s still clearly in the interests of a worker council to produce things that people went and took off the shelves at the consumption centre instead of left there. Because if it’s left there, then the question becomes we approved you to use these socially costly productive inputs based on the assumption that you were going to generate a certain amount of social benefits as outputs. So that’s the basis upon which you were approved to go ahead and do what you’ve done.

But if it turns out that what you claimed you were going to generate in social benefits was actually not the case, because when there were clear signals that people wanted red toes not yellow toes you just decided you didn’t care and you kept supplying the yellow toes; the answer to that is well when worker councils deliver stuff to distribution centres, if those distribution centres discover that the stuff is still sitting on the shelf, and it could sit on the shelf for two different reasons (1) it actually was defective or low quality or (2) it was a yellow toe and nobody wanted yellow toes. And it doesn’t make any difference, the whole point is that you didn’t deliver what we were counting on and approved you for.

So in the end when you’re looking to see whether a worker council has fulfilled its responsibility, in the end the proof is in the pudding. In the planning phases we were all taking everything on good faith, but in the end if it turned out that you weren’t in good faith then you will end up getting penalized by what we’ve proposed.

Now, there are two possibilities. One is the only thing that matters is whether your SB/SC ratio is one or higher. It could be that you were approved because it looked like it was one, but now at the end of the year we discover it was not one, it was less than one. Well, in that case there’s going to be some sort of penalty and the penalty will have to be that the average income that you get to distribute amongst yourself is less than it would have been. The other penalty is if you get caught doing this time after time after time, well then you might have your approval to participate as a legitimate trustworthy worker council in the entire planning procedure challenged, if this turns out to be a problem.

So there are there are ways of handling this. If we had a system where your average income for the year depends on that SB/SC ratio, it doesn’t matter if the plan you submitted is one where it would have been 1.05. If it turns out not to be 1.05, then the average income from for your enterprise isn’t 1.05 anymore. It’s whatever it turned out to be.

[ATO] I would query whether the only important point is that people are only getting income in proportion to the sacrifice that they make. Now, I actually think that in general the parecon argument of remuneration according to sacrifice is a very good argument. But what I mean is that there are many factors to consider. And I’m not actually saying this to disagree with what you said, but just to comment on it.

If we have a socialist society which cannot, for example, provide proper consumer goods to people that is a disaster for so many different reasons. But it’s also a social harm. I mean, the goal of an economy is to satisfy the wants and needs of people. It’s not necessarily unfair to consider that a worker’s council’s income will be slightly bigger to satisfy that need. Now, for me I suppose that the question is limiting that to make sure that you don’t have a society where people are getting paid according to how much they produce and that is the main norm.

[RH] First of all, I completely agree with you. One of the failures of – I mean, we can debate whether to call it socialism or not – one of the failures of the existing socialist societies. That was one compromise in terms of language: let’s just call in the existing 20th century socialist economies, that way you can say well they were existing but they weren’t really socialist.

Whatever you want to call them, it is clear that one of their failings was that consumers were disenfranchised to an extent that was highly undesirable. So, on the one hand, it’s important for us to look and see whether or not our actual proposals for how a participatory economy would operate meet up to the challenge of making sure that consumers have been fully enfranchised. But that was certainly a goal that we had firmly in mind. Now just because you think you have a goal friendly in mind doesn’t mean you propose something that would achieve it, I understand that. And that’s one of my admonitions to everybody that’s in this line of work, which is there are two steps, not one. The first step is being very clear about what you’re trying to achieve, and the second is just because you’re clear about what you want to achieve doesn’t mean what you’ve proposed will actually achieve that.

And so the hard work comes from testing to see. And what we’re talking about here is basically testing whether or not what mainstream economists call consumer sovereignty would be an adjective you could just you know that you could you could realistically ascribe to a participatory economy. But there’s a lot of features you know where I think that it measures up.

We have consumer federations – we have empowered consumers by basically giving them these federations that will go to battle on their behalf when products are not what the consumer expected. So instead of individual consumers – we’ve talked about this – having to go to the complaint department at the department store of a multinational corporation to get satisfaction over the fact that the damn thing didn’t work, and I should get all my money back, all you have to do is just say no this is unsatisfactory and give it back to the consumer federation. And my consumer federation goes to the worker federation to settle the issues.

I think that’s an important thing when we’re talking about the coloured toes on the footwear that are coming out of the worker council. Clearly if the red toes are not being picked up and the yellow toes are, and one of the worker councils just doesn’t respond and continues to supply the red toes, well there are procedures where you don’t get credit for that. If you deliver something that’s defective, if you deliver something that wasn’t the colour people wanted, then you’re not going to get credit for that as part of the social benefits that you generated, to be compared with the cost of the inputs, and the machines, and the things that you used to do it.

Now, exactly how they’re going to be penalized, that’s where we’re talking about the sort of nitty-gritty details and the pros of cons of penalizing one way or another. But one way or another there’s going to be a penalty for that, for any worker council in a participatory economy. And I think that’s the important thing for anybody looking at the system and asking ‘do I think this system would be satisfactory from the point of view of embodying the principle of consumer sovereignty?’. We have answers, even if those answers in some cases are multiple and there’s disagreement about whether this way to do it or that way to do it would be a little bit better, what the pros and cons are.

[ATO] I just want to make one clarifying remark on that and then we can move on to another question. We were joking about the name ‘size 6 purple women’s high-heeled shoe with the yellow toe’ problem. I just wanted to make a comment that the purpose of that particular example was to pick something that was deliberately finicky and to think about whether parecon will be able to handle such finicky preferences. But that’s not what the stakes are it’s not just …

[RH] Well, let me clarify. This is a ticklish subject because it can get me into hot water with feminists so I want to defend myself. You don’t realize that there would be feminists who would already have taken umbrage at the example we picked.

I would just like to go on the record as saying I don’t think that’s finicky at all. I don’t think it’s finicky, and I am completely in sympathy with – who was John Stuart Mill’s mentor? – Jeremy Bentham. Jeremy Bentham’s attitude was push-pin versus poetry, we are not going to sit in judgment about what people’s consumers preferences are. So I think for somebody to have particular preferences over their shoe is absolutely fine, they have every right to have that, and the business of the economy is to satisfy that, not to in judgment on it.

So I was just trying to pick an example where there were multiple details.

[ATO] Yes.

[RH] Where the thing could differ. So there were multiple details where the thing could differ, and that example was intended to help us think through the problem of broad categories during planning versus we actually have to have detailed production and delivery. And how can you how can the necessary detail actually get taken care of if the planning was done at the level of broader categories such as women’s dress shoe? Without reference to colour, without reference to heel, without reference to all these other sort of details.

And the answer was the details get filled in during the year when the discovery process: I sent these things over, I sent over as many yellow as red toes because I had no other information to go on. But now we get feedback during the year, the yellow-toed shoes are going like hotcakes and the red-toed shoes aren’t. As long as that information is communicated to the worker councils making the shoes, and as long as there are incentives for them to respond in the perfectly obvious way that you would want them to respond to that information, then we’re okay. That’s my way of thinking about it. Then we’re okay.

But if the system isn’t communicating that information, or if there’s no incentive for the worker councils to respond to the communication of the information about whether yellow or red is more what the consumers wanted, then we have a problem. So that’s the way that I think that that should be thought about.

[ATO] Yes, that’s very important context. And the issue of categories of goods and services in parecon is a huge topic, it’s very important. I would recommend that if people want to read about this topic in particular that they – in addition to Democratic Economic Planning – should read Anarchist Accounting by Anders Sandström and he really goes into detail and it’s worth reading.

And I just want to say yes, the way you phrased that I used the word ‘finicky’, you put it in a much more neutral and I think accurate way. I just want to make it very clear I am clearly no stranger to peculiar sartorial tastes …

[RH] Point well taken! Your listeners can’t see you but I’m seeing you on a video screen and man this guy dresses funny folks, he does.

[ATO] Well, they can see me on YouTube.

And I certainly would not pass judgment on women for liking shoes any more than any other person, which of course is ludicrous. What I more mean is I’m thinking of the person who might be listening in and thinking oh well look we’re talking about shoes, whether men or women, or what colour stripes they have, compare this to climate change or compare this to all these big issues. It can seem like that might just be finicky or a little bit trivial – consumerist problems.

I just wanted to make the point that – I think you made a very good point there, which is that look we have these preferences and that’s fine and we need to deal with that. But also I want to make the point in addition to that which is look if you don’t like the example of the purple shoe with the yellow toe, this applies across the board. You can think about any kind of consumer good, and even intermediate goods. The point is that goods and services when they’re delivered need to be what people want, whether that’s something used in the production process or that’s a final good used by a consumer. And that could be a shoe, it could be something that this hypothetical person might think is much more important. So the issue can’t be dismissed really, that’s the point I wanted to make.

But just to move on …

[RH] Let me say something on what you just covered before you move on. This is relevant to what we’ve just been talking about.

In some ways, I think that socialists may try to make a virtue out of the failure of centrally planned economies to provide consumers with the variety of choices the consumers wanted. And they sort of portrayed this as oh well that’s only bourgeois individualism. I mean the truth of the matter is that if we give you a good working shoe, there’s no difference between one working shoe and another. And it’s only in capitalism, when you have profit maximizing enterprises that are trying to prey [on consumers], that they’re the ones who are creating these notions in your head that their working shoe might be a little bit better or different than somebody else’s working shoe.

I think that if there’s actually a difference in the cost of society of making one working shoe compared to another that’s fine. And if you want the one that’s a little more expensive, we’ll charge you for that one. And if you want the one that’s a little less expensive, we will charge you less for that one. So you can decide how finicky you are about your working shoe. But it shouldn’t just be us telling you that you have no preference over what working shoe that you’re getting. Because we have a historical responsibility to own up to mistakes, I think this is an important thing to go on a record on [about]. I think we need to go on record, people have a right to hear us go on record, and we’re attempting to do so on that subject.

[ATO] Yeah, there’s a space somewhere between consumerist insanity and brainwashing, and distortion of the human personality, and really the manufacture of infinite desires and cravings, and homogeneity and dissatisfaction of human wants and needs in consumer goods. There’s a rich space there and somewhere in the middle in that space is where we want to be.

[RH] And you could argue that we’ve created a society where seeking pleasure in some areas has been precluded, like seeking pleasure in self-managed work, and therefore people therefore seek pleasure in other areas. And that might be being overly concerned about slight differences in the things they’re consuming. So you can recognize that that may have happened in capitalism, and that’s part of the reason that people do pay as much attention to [consumer goods]. But anyway we’re on the same page about the fact that the job of the economy is to give people what they want.

[ATO] Indeed.

Just about the social benefit and such cost issues again. If we just briefly touch on this, you were talking about modelling using a socially responsibility constraint of social benefit divided by social cost is equal to one – social benefit equals cost – as simulating a kind of possible but conservative case. A kind of worst case scenario of the scenarios where things would actually function in parecon.

And I just briefly want to talk about something which is very important, which is the difference between modelling a participatory economy (as in simulating it), to designing a participatory economy (as in how it’s supposed to work, how it’s intended to work), and the actual behaviour of a participatory economy. And I plan to ask several questions at a later time about the simulations in Democratic Economic Planning, so we can talk at length then. But if you just want to comment on that difference.

[RH] This has to do with the sort of worst case scenario. I think there’s a useful purpose to modelling something where you assume an actor will do what is in that actor’s individual self-interest. And that’s not because people always choose to behave in their own individual self-interest. People often take the interests of others into account when they choose what to do. But I’m interested in evaluating what kind of behaviour institutions are going to generate or what is the effect of an institution. And if I want to know what the effect of an institution is, one way to answer that question is well in the context of that institution what would it be in the self-interest of actors to do?

So I don’t think of it as a predicting issue. I don’t think of it as we’re trying to predict what people are going to do. And I certainly don’t think that people are homo economicus. I don’t think humans are little self-interested machines. But I do think that what we’re doing is designing economic institutions. And if you want to know what kind of behaviour an economic institution is going to generate or encourage, then the way to do that is to say well what would be rational behaviour for actors in their own self-interest if you put them in that context? So that’s the reason that I do that kind of modelling and that’s the way I interpret what it is that I’m doing.

You can also see it as a kind of a worst case scenario, that here we have these institutions and what’s the worst case scenario behaviour that they could generate, that could come out of this? And in some sense the answer to that I think is well if everybody behaved in their own self-interest this is what we would get. And if we can design institutions so that even in a worst-case scenario what we get is something that looks like it would be fair or looks like it would be efficient, well then in some sense that makes the argument more powerful.

Because I know that a lot of people from the socialist tradition take umbrage at the whole idea that we’re going to be modelling things in ways in which we’re thinking about people behaving in selfish ways, whether it’s workers in their councils or consumers. That somehow, if you do that, you are maligning the best of humanity. And just despite the world’s sorry history, I continue to have great faith in the best of humanity, and I see it operating every day despite all sorts of disincentives to behave in solidaristic ways. But that’s not my point it’s not a comment about humanity. It’s a comment about what we need to take into account when designing institutions.

[ATO] Last time you were saying that in a particular modelling and simulation exercise you decided to impose a constraint that for a firm social benefits had to equal at least equal to social costs and that the workers would try to maximize their utility, or minimize their disutility of working. And what you’re saying there is you weren’t necessarily saying this is how I think humans behave or this is how parecon is designed to operate, but you’re saying if this happened in parecon what would be the consequences? Would it still function?

And in engineering terms you can think about that as a kind of fail-safe. Everybody knows the word fail-safe. So if you’re designing an airplane, for example, if you’re designing, say, sensor for an aileron, if that fails is it going to just lock into a position that it sends the plane into a nosedive? Or is it just going to settle into some kind of neutral state where at least it doesn’t cause a catastrophe? And it’s a similar idea.

[RH] I think that’s a very apt analogy. I think that’s exactly right.

The other thing about the modelling was again it’s a case of a worst case scenario or it’s pushing something to the limit. In my view, one of the big errors that socialism made historically was in not taking seriously enough the importance of people engaging in self-management, particularly workers. so if you want to counteract that mistake, one way to do it is to say we want the workers and the council to do whatever they want and we want consumers to do whatever they want. Well, that can’t exactly be true. We can’t really just let everybody do exactly what they want. That doesn’t work. It wouldn’t be right, it wouldn’t be efficient, it wouldn’t be fair. It would be wrong for all sorts of reasons.

But what if we simply say the only constraint that you have to deal with when you are deciding what you want is you can’t make everybody else worse off? And that’s essentially why the social benefit to social cost ratio has to be at least one. That’s basically what that constraint comes down to. So I’m not really saying that’s the way we want to run the economy, but at least it puts us in a situation where we’re almost going to the opposite extreme from what I view as being one of the historic errors that socialism made in terms of not taking nearly seriously enough providing opportunities for [worker self-management].

Consumers have had their defenders. It’s interesting that given the history of our economies, and because we’ve had market economies the whole idea of consumer sovereignty, nobody should be dictating to consumers what they what they consume they should be deciding what they want to consume, that’s a very, very, popular idea. That part has sunk in.

But the whole idea among socialists at least that workers in their own councils should be in charge of deciding what they do … And one manifestation of this we’ve talked about was the [Pat] Devine – [Fikret] Adaman proposal, where the workers in the councils don’t even get to sit down just amongst themselves to even begin the discussion about what they want to do. We have to have these other affected parties that are on the board of directors, etc. So, in part it’s sort of a response to that, as recognizing from history that we have under-provided adequate ways for workers in their workplaces to make their own decisions, to talk about things amongst themselves before they have to deal with anybody else, and make their own decisions about what they want to do as long as they’re being socially responsible. Why not? So that was the motivation for modelling it exactly in that way.

[ATO] Thank you for watching. If you got anything from this video, then please press the Like button, consider Subscribing, and, if you really enjoyed it, then make a reaction video of you half watching it while playing a computer game.

There’s a lot more to come. We’ll keep exploring better futures for humanity until we get there. And as always I want to hear your thoughts in the comment section below. This channel has a wonderful audience and there are usually some very interesting comments under the video, so let’s continue that.

That’s all for now. Our democratic future lies After the Oligarchy.