Nikos Kanarelis, director of the cultural sector of mέta, argues for the potential of art to illuminate what remains silenced and to transform people’s thinking.

Nikos Kanarelis, director of the cultural sector of mέta, argues for the potential of art to illuminate what remains silenced and to transform people’s thinking.

We are facing a crossroads where capitalism, as an inherently unstable system, is dying, but the alternative to barbarism has not yet emerged, reminds us the vice-president of the Board of Directors of mέta Sissy Velissariou.

Dr Sotiris Mitralexis, director of mέta’s academic sector, points to the uncertain transition from the existing economic, political and ultimately anthropological international order to something dystopian — or, potentially, eutopian.

Here you may watch Mark Blyth’s lecture ‘The Euro – an assessment in the midst of a European war’ with a Q&A with Yanis Varoufakis and the audience, in the context of mέta’s colloquium “20 Years of Euro: An Assessment in the Shadow of a European War” (full video here).

The introduction of the euro (exactly twenty years ago as Greece’s currency) was presented as a big promise of economic convergence and well-being, in the spirit of the even bigger promise of permanent peace in the European continent. However, as is all too evident by now, the euro was instrumental in dividing rather than uniting Europe, and it put in action centrifugal forces that undermined unification – a prerequisite for a common European foreign policy and defense policy. Today, in the context of the biggest military conflict on European soil since decades, a critical re-evaluation of the twenty-year-long history of the common currency is more urgent than ever. In the colloquium organised by mέta on the 16th of April at Athens’ Technopolis’ we analyse the introduction of the common currency, its impact during the last two decades, its geopolitical, ideological, and cultural dimensions while contemplating alternatives in the era of digital money.

Mark Blyth, a member of mέta’s Advisory Board, is the William R. Rhodes ’57 Professor of International Economics at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University. Mark researches the political power of economic ideas as seen in his books Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2002) and Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea (New York: Oxford University Press 2015). He also researches the political economy of Europe and the US as seen in his 2015 book The Future of the Euro (New York: Oxford University Press 2015), Angrynomics (New York: Columbia University Press 2020) and in his forthcoming book on the politics of economic growth (with Lucio Bacarro and Jonas Pontusson) The New Politics of Growth and Stagnation (Oxford University Press 2022).

We welcome Professor Mark Blyth to mέta’s Advisory Board!

Mark’s view on postcapitalism – a contribution to mέta:

I really wish that I didn’t have to think about postcapitalism, but we do. It’s hard to think past something that is so encompassing and every day. But it’s precisely because capitalism has reached into so much of our lives, commodifying everyone and everything, that we need to think about a world that’s different.

Imagine a world without billionaires and oligarchs deciding what policies governments will pursue before you every get to vote on them.

Imagine a world where those elected to do something about the climate catastrophe actually dare to tackle the forces of carbon denial and deadly profit.

Imagine a world where housing is something that you live in rather than yet another asset class for the already-rich to dominate you.

Imagine a world where we do not allow entire sectors of the economy to become rent-generating cartels, and where we do not allow our social lives and the infrastructures that they rely on be sold-off to the oligarchic class.

Imagine a world where investment grows jobs and the incomes of ordinary people rather than disappearing into the Boardroom via stock buybacks or into financial speculation.

I actually can imagine that. It’s really not that difficult to do so. But we seem to be served by a political class that cannot see what we can see. Our job is to clarify their vision and demand their action. And if they continue to fail, to replace them. That to me is what postcapitalism actually looks like. A fair and functional and carbon-free economy where your vote and your voice actually counts. It’s not a revolution really. More a restoration of a system that has gone seriously off the rails.

Mark Blyth is the William R. Rhodes ’57 Professor of International Economics at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University. Mark researches the political power of economic ideas as seen in his books Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2002) and Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea (New York: Oxford University Press 2015). He also researches the political economy of Europe and the US as seen in his 2015 book The Future of the Euro (New York: Oxford University Press 2015), Angrynomics (New York: Columbia University Press 2020) and in his forthcoming book on the politics of economic growth (with Lucio Bacarro and Jonas Pontusson) The New Politics of Growth and Stagnation (Oxford University Press 2022).

During the pandemic he learned to play the drums. Doing so gave him osteoarthritis in his thumb. All of which proves that no good deed goes unpunished.

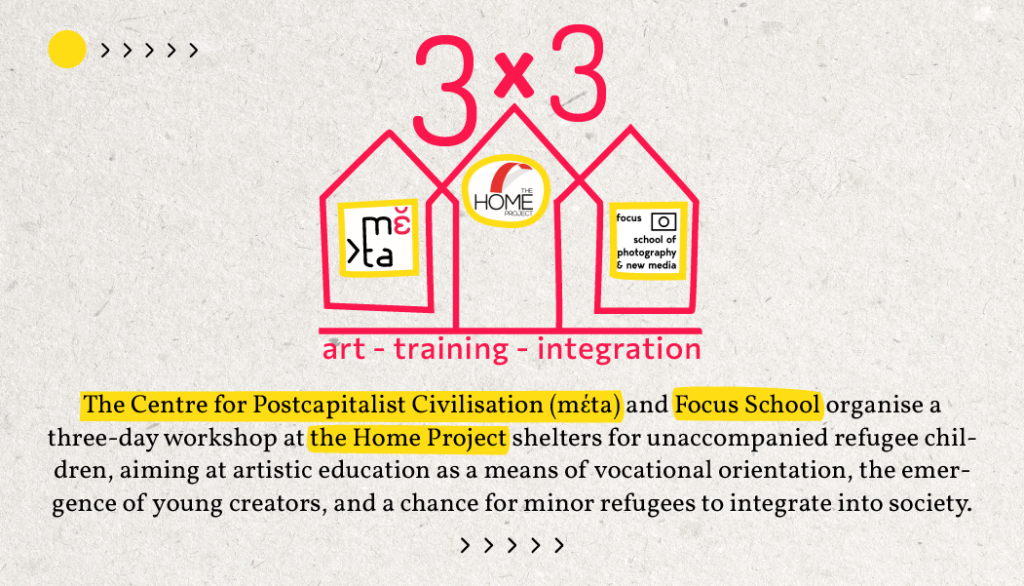

mέta (Centre for Postcapitalist Civilisation), Focus Photography School, and The HOME Project unite in a three-party collaboration with a triple goal: the promotion of art education, namely photography, as a means of vocational orientation, the promotion of new creators, and the unobstructed integration of unaccompanied minor refugees.

The pilot project “Photo-Workshop in the HOME Project Shelters”, scheduled for a three-month duration, enables interaction between professors and students of Focus School and accommodated children, as well as a broader audience, in the framework of a process of mutual enrichment in professional or pre-professional skills, a process of refinement of empathy and intercultural approach, too.

In numerous consecutive sessions on the School’s premises as well as in The Home project shelters, supported by their professors, the photography students elaborate a seminar circle of courses in the framework of their internship, addressing the accommodated children, and work on cooperatively created material produced gradually, aiming at an exhibition of the original product as well as the compilation of snapshots from all stages of the cooperation. Great significance is allocated to the proper preparation of the artists, students, and professors, before their admission to the shelter as well as to the continuous monitoring mechanism, driven by The HOME Project mental health specialists. The experienced personnel of the shelter will be present at any given time during the courses.

Not only is mέta’s involvement in such a project a gesture of moral and practical support to the valuable work The HOME Project is contributing, but it also serves as experimentation in the field of creative commons and the empowerment of the beneficiaries, which constitute basic pillars of its policy.

Constantly pursuing the dialogue between art and political endeavour, the Centre for Postcapitalist Civilisation (mέta) proceeds with a series of films regularly screened in the multi-space facility of Mikrokosmos, literally bringing in the centre of our attention a genre connected per se to this pursuit: cinema.

With the kind contribution of Greek and foreign creators, who, quite often, work in stifling conditions, mέta proposes to a wider public significant, recent film productions, which visualise but also critically problematise various aspects of the multi-faceted crisis surrounding us, as well as pinpoint emancipatory alternatives. For, quite often, optical language proves to be much more eloquent than numerous written pages, in the depiction of societal reality – at times, riveting.

The beginning of this, hopefully, the multi-month trip is on 12th February 2022, at 17:30 with Digger. The several awards winner film of Georgis Grigorakis, nominated for 14 prizes at Iris Awards of the Hellenic Film Academy, though typically a fiction product, constitutes a valuable attestation to the violation of Greek Nature, the subversion of social relations, and, what is more, the ignition of primary resistance, in view of the violent advance of the mining industry that the (meta)memoranda dystopia presents us as a royal way of “growth”.

A Q&A session with the director and contributors to the film will follow.

mέta is a civil-non-profit research and cultural institution, related to the political party MeRA25, the European movement DiEM25, and Progressive International. It was established in 2020, aiming to explore eutopic alternatives to the postcapitalist era in which we are already living, through academic and cultural actions regarding the political, social, economic, ecological, cultural, and civilisational challenges of our times.

Cine Mikrokosmos (member of Europa Cinemas) was born in the fall of 2004, on Syngrou Avenue, opposite ex-Fix Industry, equipped with state – of the – art technology and with a unique architectural approach. Having hosted numerous festivals and tributes, without ever standing off from first-rate promotions, committed to cinephile choices, and particularly hospitable to independent Greek productions, Mikrokosmos has created its own audience and is chosen for its ideal show conditions, its careful selections, and, occasionally, for its autonomous bar, which operates in the foyer at affordable prices and cinematic ambiance.

Giorgis Grigorakis is a film director and scriptwriter, with his first Degree in Social Psychology and MA in Film Directing from the National Film & Television School (NFTS) in London, and alumnus of Berlinale and Sarjevo Talent Campus. He has written and directed numerous short films, which have gained international attention and awards, in over a hundred film festivals in which he participated.

DIGGER, his first full-length film, was developed by means of Nipkow, Cannes Cinefondation Residency, and Sundance Institute scholarships.

It premiered at the 70th Berlinale where it won the CICAE Art Cinema award, was awarded the Best Actor Award in Sarajevo, and continued its successful career in internationally recognized festivals around the world (AFI, Busan, Melbourne, Philadelphia, São Paolo, Haifa, Ghent, Goteborg among others). It won the Special Prize of the Committee – Silver Alexander and four more awards in Thessaloniki. It won 10 Iris Awards from the Greek Film Academy (Best Film, Best Director, Screenplay).

mέta team

Michael Albert and Yanis Varoufakis, members of mέta’s Advisory Board, take part on an ongoing debate on how a postcapitalism worth striving for could look like. Here is their latest exchange; the whole discussion, to be constantly updated and enriched, is to be found here.

Michael Albert’s third response:

Yanis, self-management doesn’t mean Tom can’t do things that impact others. It only means everyone should influence decisions in proportion as they are affected. For self-management an affected group that decides some issue may be a whole council, a team, or even an individual. For different issues, self-management may need more or less deliberation and require different ways to tally preferences into decisions. You ask who will determine what decision-making methods and procedures workplaces use. The workers council, of course.

Make telegraph machines no one wants? Make wheels for vehicles no one drives? Consume all you want oblivious to what others want and to the size of the social product? No society can allow each person to decide these sorts of things on their own. So how do we make sure everyone gets a say proportional to how decisions affect them? If just you are affected, you decide. If just a group is affected, the group decides. And decision-makers always use procedures that best convey proportionate say.

So of course Harriet decides what job Harriet wants to do. But how? Harriet’s workers council assesses workplace tasks and apportions them into jobs balanced for empowerment. Harriet applies for a job she likes. If Harriet is ill-equipped for her preferred job, Harriet’s council won’t accept her application because her working at that job would be socially irresponsible. So, yes, Harriet chooses her job, but she chooses it from among jobs the workplace offers that she can do well.

Do you really think Harriet should instead “pursue projects without anyone’s permission”? That would imply that Harriet can utilize resources, inputs, and tools however she pleases. She need not be competent. She need not fit the environment of her workplace. She can waste tools, time, and space making telegraph machines no one wants. She can produce wheels for vehicles no one has. And what about other people with other ideas for how to use the tools, time, and space Harriet would be commandeering? I wonder, do we differ about how to combine individual freedom and creativity for each with individual freedom and creativity for all?

Switching to remuneration, you ask, “who will decide what constitutes socially useful work?” Well, does anyone want the product? If not, producing it was not socially useful. Did the production responsibly utilize resources, tools, labor, and other inputs? If not, not all the work was socially useful. Thus the whole population together decides what is socially useful via allocation we have yet to discuss.

Finally, the guaranteed basic income you favor is possible but not necessary in a participatory economy, though getting a full income while moving between jobs or if you can’t work is necessary—but a full income, not a “basic income.” I wonder if the democratic planning you favor is markets plus democratically chosen policies to mitigate market failings. If so, I instead prefer participatory planning without markets at all.

Yanis Varoufakis’ third response:

Michael: To my question “Who decides if Harriet is allowed to choose her projects?”, you responded: “the workers’ council, of course”. To the question “Who decides what product or activity is socially useful?”, you replied: “the whole population together decides”. My gut reaction to your answers is a gut fear stemming from a natural dread I have of, as liberals and anarchists put it, the tyranny of the majority. Then again, democracy is only possible if the demos decides. The question is: Can democracy-at-work be made compatible with a degree of personal autonomy from what the majority thinks?

At this point in our discussion we need to set out concrete rules for the governance of enterprises. Here are five that I would like to propose:

i. Democratic planning

Competing enterprise plans are put forward by members, each accompanied by a full rationale. They include how many resources to commit to R&D, which product or technology to invest in, the level of remuneration etc. Members are given a long period to read up on each proposal, to debate them and to form preferences. They are then invited to rank the proposals in order of preference on an electronic ballot form. If no plan wins an absolute majority of first preferences, a process of successive elimination takes place (based on Australia’s ranked preference electoral system) to determine the winning Plan.

ii. Autonomy

Teams are formed (as per the Plan) by a democratic process that matches slots with applicants. No one is compelled to take a slot they do not want. Each retains the right to work, alone or in spontaneously formed teams, on any project she or he deems compatible with the Plan – without anyone’s permission.

iii. Remuneration

A basic salary is paid to all, whose level is decided democratically as part of (i) above. Additionally, the collective can set aside a sum for two types of bonuses: (A) Job-specific; i.e., the collective decides that an X% bonus is right, reflecting the job’s unpleasantness or high skills necessary. (B) Person-Specific; i.e., a reward for extraordinary services to the enterprise’s overall performance, atmosphere etc. For example, each member is given 100 brownie points to distribute amongst her colleagues across the enterprise. Then, the total Personal-Bonus kitty is divided in proportion to how many points a member has received from everyone else.

iv. The right to quit – and the right to a basic income

To be genuinely free and an authentic participant, a worker must have the right to walk away from a company if she feels the majority is stifling her. To render this right real, as opposed to theoretical, the worker must have an ‘outside option’. This is why an unconditional basic income (guaranteeing a life with dignity) for all is not an optional extra for the good society – but a fundamental obligation to its citizens

v. The right to fire – and the right to a basic income

At the same time, for the majority to be free from toxic individuals, the collective must have the right to fire (by democratic vote) a member abusing her autonomy – a right that the collective can only exercise if it knows that everyone has the right to a basic income guaranteeing a life with dignity.

Over to you.

This is an ongoing debate between Michael Albert and Yanis Varoufakis: more entries will be added here soon.

Watch the recording, with English subtitles, of mέta’s event “What comes after capitalism? A discussion on P2P and the digital commons”, a discussion between Professors Vassilis Kostakis and Yanis Varoufakis on P2P and the commons (moderation: Sotiris Mitralexis):

Discussants:

Vasilis Kostakis & Yanis Varoufakis

Monday, 15 November 2021, 7pm

P2P production and the digital commons in an era of nascent postcapitalism(s).

Vasilis Kostakis is Professor of P2P Governance at TalTech and Faculty Associate at Harvard University‘s Berkman Klein Center. Moreover, he is the Founder of the P2P Lab and a founding member of the rural makerspace Tzoumakers (Tzoumerka, Greece). Vasilis is interested in exploring how to create a sustainable post-capitalist economy based on locally productive communities that are digitally interconnected.

Yanis Varoufakis is a member of the Hellenic Parliament, the Secretary-General of MeRA25, and a professor of economic theory at the University of Athens.

Serafeion, Pireos & P. Ralli, Athens 118 54, Greece

Michael Albert and Yanis Varoufakis, members of mέta’s Advisory Board, take part on an ongoing debate on how a postcapitalism worth striving for could look like. Here is their latest exchange; the whole discussion, to be constantly updated and enriched, is to be found here.

Michael Albert’s second response:

Yanis, you say our differences begin beyond our both rejecting capitalism, advocating a productive commons, favoring participation in planning, and seeking to replace the “coordinator class.” But do we agree that to end coordinator class rule we need to replace the corporate division of labor with jobs balanced for empowerment? Do we agree that we should all decide our lives up to where our choices impinge on others, but from there on, others should have their self-managing say, as well?

You express alarm that I use the words “equitable” and “negotiation.” You worry that these words may hide new forms of domination. But “equitable” means we receive income for how long, how hard, and the onerousness of the conditions under which we do socially useful work. Why would that alarm you? The only thing equitable remuneration has in common with market remuneration is that in each you get an income. But with markets you get what you have the bargaining power to take. With equitable remuneration, you get what you and your fellow workers decide accords with your duration, intensity, and onerousness of socially valued work.

And regarding “negotiation,” I assume you agree that any economy will and should involve people acting jointly with other people. Doesn’t it follow that in worthy postcapitalism, a worker won’t just do or get whatever they alone choose? Call what they do together exploration, conversation, or negotiation, what’s the alternative? One person or a small class decides? Competition decides?

You don’t want people telling you what to do. Okay, but people telling you what to do seems a strange way to characterize decisions that you participate in. In any event, do you think there could or should be a society where each person would decide their own remuneration, their own consumption, and their own work, with no concern for others?

You say you find suffocating ”the prospect of having to reach via negotiation a common understanding of what [you] must do and of what an equitable reward is for [you] to do it.” In participatory economics no one tells you what you must do and you are part of who decides what is an equitable reward. You are a participant in society, not atomistically aloof from it.

You have a job. Suppose your workers’ council, of which you a full member, decides when the work day starts. It sets council agendas, it determines the composition of balanced jobs, and it decides how to apportion income among its workers. Assume mutually agreed sensible deliberation plus self-managed decision making procedures. Would that be suffocating? To achieve “a degree of autonomy from the collective,” participatory economics makes diversity a prime value and emphasizes the need to respect and even preserve minority positions. But shouldn’t post capitalist division of labor, decision making, remuneration, and allocation deliver goods and services but also solidarity, diversity, equity, self management, and sustainability? We haven’t yet explored how all that can happen, but can we agree it needs to happen?

Yanis Varoufakis’ second response:

Michael: Glad that we are proceeding slowly, refusing to take for granted vague terms like ‘equitable’ and ‘just’ – terms within which all manners of oppressions and irrationalities can take refuge. Before proceeding, and in the interests of full disclosure, let me state it for the record that, from a young age and to this day, I have signed up to Karl Marx’s dismissal of equity (as a bourgeois notion) as well as to his antipathy to defining freedom as the right to make free choices as long as they do not impinge on others.

So, when you ask me whether we agree “…that we should all decide our lives up to where our choices impinge on others, but from there on, others should have their self managing say, as well”, my response is: No, we certainly don’t. Interdependence is a given in any social network. Thus, according to your definition of freedom, every Tom and Dick has the right to scream that Harriet’s choices somehow impinge on theirs. Who will adjudicate then? Tom and Dick, merely because they are in the majority (or any majority for that matter)? That is unacceptable.

You ask me why I am alarmed by your definition of equitable: “…Equitable means we receive income for how long, how hard, and the onerousness of the conditions under which we do socially useful work.” The answer is because I shudder to imagine who will decide what constitutes ‘socially useful work’. What happens if Harriet wants desperately to work on some new project that Tom and Dick consider ‘socially useless’? Or who gets to quantify how hard or onerous a particular job is? The majority again? Just writing these words makes my throat choke with angst.

You ask: “Do we agree that to end coordinator class rule we need to replace the corporate division of labor with jobs balanced for empowerment?” Sure, we agree. But, who gets to decide the job balance necessary for Harriet’s empowerment? My answer is: Harriet. No one else. Not Tom and Dick. No worker council should tell Harriet what is good for her to do, let alone decide on her behalf. Sure, they can chat about it in the assembly, on the company’s intranet, via all sorts of teleconferences etc. But, unless Harriet gets to decide what Harriet does, it ain’t self-management.

Naturally, the question then becomes: How do things that need to get done get done? I have concrete ideas on how to answer this all-important question. But, in the spirit of taking this conversation slowly, I shall begin by setting down five basic principles that enterprises should adhere to:

Authentic self-management: Participants (i.e., worker-co-owners) must be free to join at will, or to quit, work teams within the enterprise – and to pursue projects without anyone’s permission

Democratic hiring & firing: A democratic process must determine who is brought into the enterprise, but also who is fired (Nb. The right of the collective to dismiss a participant as a necessary counter-balance of authentic self-determination)

A basic income for all: Without an adequate basic income, to fire a participant is to jeopardise her capacity to live. This would vest too much power in the hands of the majority (within the enterprise) while, at once, making it harder to fire someone that deserves to be fired.

Democratic resource allocation: The collective decides how much the basic salary is, how much to spend on infrastructure (including R&D), the enterprise’s multi-year plan and, lastly, how much to set aside for annual bonuses (to be distributed according to a democratically agreed process)

Your thoughts?

This is an ongoing debate between Michael Albert and Yanis Varoufakis: more entries will be added here soon.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-functional | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". | |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-others | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. | |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Advertisement". | |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". | |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". | |

| viewed_cookie_policy | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __atuvc | This cookie is set by Addthis to make sure you see the updated count if you share a page and return to it before our share count cache is updated. | |

| __atuvs | This cookie is set by Addthis to make sure you see the updated count if you share a page and return to it before our share count cache is updated. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| uvc | The cookie is set by addthis.com to determine the usage of Addthis.com service. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| loc | This cookie is set by Addthis. This is a geolocation cookie to understand where the users sharing the information are located. |