What we like

‘Civilising a hugely irrational world’

One year since the final deal for Brexit was announced, it remains one of the most divisive political subjects for a generation. Perhaps unknown to most, the incendiary B-word had its genesis in the term “Grexit” — coined during tumultuous years after the 2008 credit crunch when a Greek exit from the EU was speculated, as the nation’s people suffered punitive austerity measures imposed by the “troika” of EU Commission, central bank and IMF.

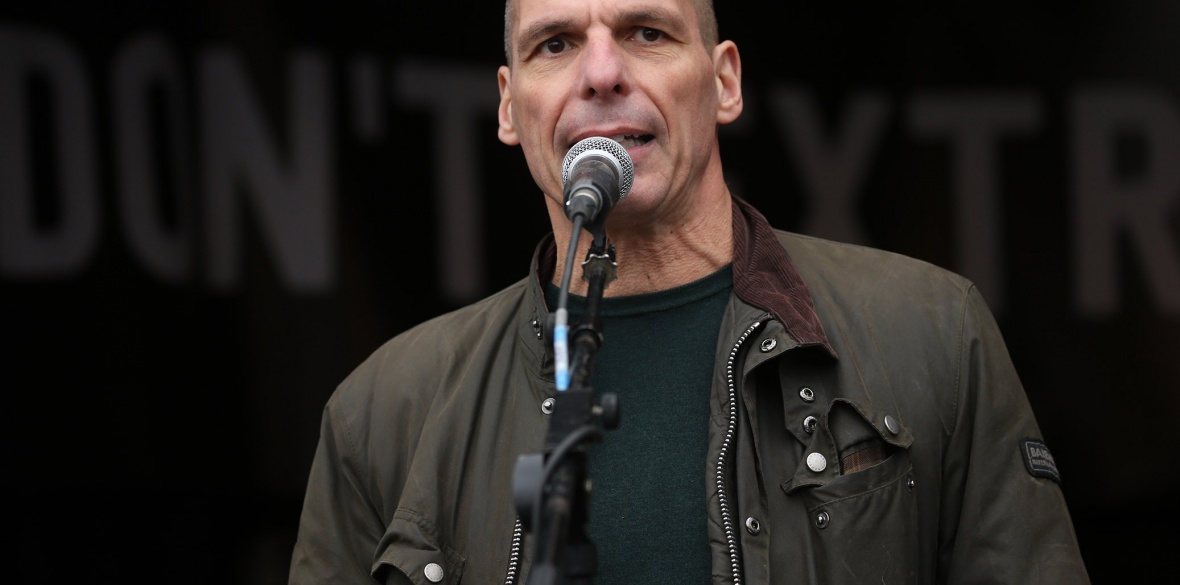

After subsequent periods of mass civil unrest, rioting and national catastrophe, the democratic socialist party Syriza was elected in 2015, with Yanis Varoufakis serving as finance minister during crucial crisis talks with the deep establishment of the EU, as dramatised in the 2019 movie Adults in the Room.

Varoufakis became a familiar face in British media during the Brexit period and expresses dismay concerning some of the dogma surrounding the debate.

“Undoubtedly, the hard Remainers were as unsophisticated in their narrative as the hard Brexiteers. Mirroring the latter, for whom the EU was the source of all evil, the hard Remainers portrayed the EU as a splendid utopia — and in so doing they did enormous damage to the cause of Remain.

“The case of Greece is, as you imply, a useful case in point: we ended up with the absurd situation where Tory grandees were lambasting the EU for imposing on our people overly harsh austerity and for snuffing out our radical left government, while hard Remainer Labour functionaries were keeping silent.

“Personally speaking, it was utterly confounding to be shunned by social democrats and be embraced by Tories even though I was campaigning against Brexit and in favour, alongside Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell, of a radical Remain.”

Many Remain voters perceived EU freedom of movement solely as a beneficial piece of legislature with attractive rights offering work or study abroad, yet this pillar of the single market also enabled unscrupulous British employers to undercut domestic workforces by hiring from poorer EU nations at the lowest possible rates exploitatively, causing social friction and driving wages down.

The “Posted Workers Directive” included one such loophole, belatedly closed in 2018 — two years after the referendum — but Varoufakis agrees that similar mechanisms facilitating wage competition still exist within the EU labour market.

“Under capitalism, of any variety, the legal framework meant to protect waged labour is full of holes that employers use at will. But I must insist that freedom of movement was and remains, on the balance of arguments, a progressive feature of the EU.

“Yes, labour mobility in the short run allows capital to undermine the local trade unions. But, the solution is not electrified fences and impenetrable borders. The solution is the unionisation of immigrant workers.”

A fine solution that would be, hypothetically — but after decades of legislation designed to weaken trade unions in Britain, growth of support to leave the EU was inevitable; and the trade bloc is not unfamiliar with the use of harsh border controls, since waves of migrants attempting to enter it have been tear-gassed and brutalised on the south and eastern flanks of the European continent.

But despite the punishing financial impositions placed upon the people of Greece by the EU, Varoufakis campaigned for Remain in Britain.

“The reason I opposed Brexit was both strategic and ideological — the ideological part [being] a commitment to bringing borders down so as to accelerate capitalism and give workers from different countries the opportunity and the challenge, to forge transnational organisations.

“As for the strategic part: I could see that Brexit’s referendum success would lead to a Johnson-led Tory government. Back in March 2015, in a Guardian Live event at Emmanuel Centre, Tariq Ali and I debated the issue.

“Tariq argued that Brexit would cause a rift in the Tory Party that would, essentially, lead to its final breakup. I counter-argued that the Tories are the epitome of class solidarity and, whatever differences they may have, they know how to bury them in the pursuit of the interests of capital.

“In sharp contrast, I continued, it is the Labour side of politics that will be mortally divided by Brexit. I think that life has delivered its verdict. Personally, I have little doubt that Corbyn might have ended up in 10 Downing Street if Brexit had failed at the referendum.”

However, in an interview last May with UnHerd, Varoufakis reconsidered that Brexit was “probably the right way for Britain” and reiterated his annoyance with hard Remainers who persisted in their attempts to overturn the referendum result.

Meanwhile, left-leaning Leave voters hoped Britain would now be free from EU law that stipulates compulsory privatisation of industries such as transport and energy utilities, preventing full nationalisation to exclude profiteering by private investors at the expense of workers and services provided to the public.

But details of Johnson’s final Brexit deal include a clause, Article 2.1: “The parties acknowledge that anti-competitive business practices may distort the proper functioning of markets and undermine the benefits of trade liberalisation.” Varoufakis is cynical about this.

“These agreements are not worth the paper they are written on. There is nothing binding here since it is up to the British government to interpret as it sees fit the meaning of ‘anti-competitive business practices.’

“In any case, I also believe that a government of the left had considerable degrees of freedom de facto to nationalise key industries even within the EU. Look at what happened, for example, during the pandemic: almost the whole of Germany’s economy was effectively nationalised!

“Moreover, France and Germany took advantage of the pandemic to end, to all intents and purposes, the level-playing field rules, eg by pushing through mergers against the edicts of the European Commission.”

Yet it should be considered that France and Germany are de facto EU leaders — and are thus more able to bend rules (such as the law that eurozone nations must keep deficits within 3 per cent of GDP, for breaking which Greece and Italy were punished.)

Furthermore, they were able to implement nationalisation during the pandemic because EU law permits it in cases of emergency — so it was a temporary measure only, since extending this to a permanent situation would be contrary to other EU laws that mandate privatisation, which the European Court of Justice (ECJ) tends to rule in favour of lest the rights of private investors be curbed. A reminder that freedom of movement does not concern persons only, but goods, services and, crucially, capital.

A distinguished professor and prolific author, Varoufakis theorises that traditional capitalism has been superseded by an economic system he terms “techno-feudalism.”

“Central to the thesis that techno-feudalism is distinct from capitalism is the observation that, following 2008, the rise of digital platforms and more recently the pandemic, the two main drivers of capitalism are no longer central to the economic system: profits and markets.

“Profit-seeking, of course, continues to drive most people. And markets are everywhere. However, the broad system we live in is no longer driven by private profits. Nor is, these days, the market the main mechanism for wealth extraction or creation.

“What has replaced profits and markets? The short answer is: central bank money has replaced capitalist profits as the system’s fuel and big tech’s digital platforms have replaced markets as the mechanism for value extraction.

“Central bank money replaced profits as the system’s driver: profitability no longer drives the system, even though it remains the be-all-and-end-all for individual entrepreneurs. Indisputable evidence that central bank money, not profits, power the economic system is everywhere.

“A great example is what happened in London on August 12, 2020. It was the day markets learned that the British economy shrank disastrously — and by far more than analysts had expected (more than 20 per cent of national income had been lost in the first seven months of 2020). Upon hearing the grim news, financiers thought: ‘Great! The Bank of England, panicking, will print even more pounds and channel them to us to buy shares. Time to buy shares!’

“This is just one of countless manifestations of a new global reality: in the US and all over the West, central banks print money that financiers lend to corporations, which then use it to buy back their shares — whose prices are thus decoupled from profits. The new barons, as a result, expand their fiefs, courtesy of state money, even if they never earn a dime of profit!

“Moreover, they dictate terms to the supposed sovereign — the central banks that keep them ‘liquid.’ While the Fed, for example, prides itself over its power and independence, it is today utterly powerless to stop that which it started in 2008: printing money on behalf of bankers and corporations. Even if the Fed suspects that, in keeping the corporate barons liquid, it is precipitating inflation, it knows that ending the money printing will bring the house down.

“The terror of causing a bad debt and bankruptcy avalanche makes the Fed a hostage of its own decision to print and ensures that it will continue printing to keep the barons liquid.

“This has never happened before. Powerful central banks, that today keep the system going single-handedly, have never wielded so little power. Only under feudalism did the sovereign feel similarly subservient to its barons, while remaining responsible for keeping the whole edifice together.

“Digital platforms are replacing markets: during the 20th century and to this day, workers in large capitalist oligopolistic firms (like General Electric, Exxon-Mobil or General Motors) received approximately 80 per cent of the company’s income. Big tech’s workers do not even collect 1 per cent of their employer’s revenues. This is because paid labour performs only a fraction of the work that big tech benefits from. Who performs the bulk of the work? Most of the rest of us!

“For the first time in history, almost everyone produces for free (often enthusiastically) big tech’s capital stock (that is what it means to upload stuff on Facebook or move around while linked to Google Maps). That has never happened under capitalism.

“Key to understanding our new system is the realisation that digital platforms are not a new form of market. That when one enters Facebook as a user or Google as an employee, one exits the market and enters a new-fangled tech-fief.”

Intriguingly, Varoufakis has recently proposed a universal basic income (UBI) funded via input generated by users of search engines and social media. As with any suggestion of UBI, two key questions that arise are whether this would cause inflation and whether providing every individual with an income regardless of their economic circumstances can be genuinely fairer than one devised on a means-tested basis.

“Whether it is inflationary and fair will depend on how it is financed. Unlike other proponents of UBI, I oppose the idea of paying for it using taxation. If you tell hard-working blue-collar workers, or Deliveroo drivers, that you will take a chunk of their puny income to pay layabouts and rich people, they will laugh in your face — understandably.

Similarly, such a UBI may indeed prove inflationary. However, if it is funded, as I propose, through a combination of redistributing shares (ie returns to capital) and central bank money, UBI will be neither divisive nor inflationary.

“Let me explain. First, redistributing shares.Capital was always produced socially and its returns privatised by the capitalist class. Today, this is much, much more so — as the whole of society is producing big tech’s capital (with every post on Facebook, every Google search etc), while the returns of all that capital are monopolised by capitalists.

“It is high time that we demand that a share, say 10 per cent to begin with, of the corporations’ shares be transferred to a social equity fund. Then the accruing dividends can be one of the two income streams that fund a basic income.

“Secondly, central bank funding. Since 2008, central banks have been printing mountain ranges of cash on behalf of financiers. The money tree is being plucked, in other words, daily — but the money it produces is utterly wasted (as it turns into share price and house price inflation). Here is an idea: instead of financing financiers to do untold harm, use the money tree to fund part of everyone’s basic income.

“To see why this type of UBI, which I prefer to call ‘basic dividend,’ is neither inflationary nor unjust, consider this: yes, everyone collects it without the ignominy of means testing. But, nothing stops us from taxing at the end of the year the basic income of those above a certain income at a very high rate.

“Moreover, the fact that the basic income will not push prices up in response to increasing VAT or personal taxation in order to fund it, means that it will not be inflationary per se. If, however, we do need to keep inflation under control, the central bank can reduce its use of the money tree (ie print less cash) while increasing the percentage of shares corporations must contribute to the social equity fund (ie socialise a larger share of capital).”

On the subject of positive and practical advice for activists, campaigners and supporters of the wider left and labour movement going forwards, Varoufakis mused:

“I have no words of great wisdom to offer those ‘unreasonable’ enough to want to change the world.

“Speaking for myself, life is simply not fun without trying constantly to civilise a hugely irrational world and to boot, without constantly urging our comrades to beware concentrated power (even within our own movements and organisations).”