What we like

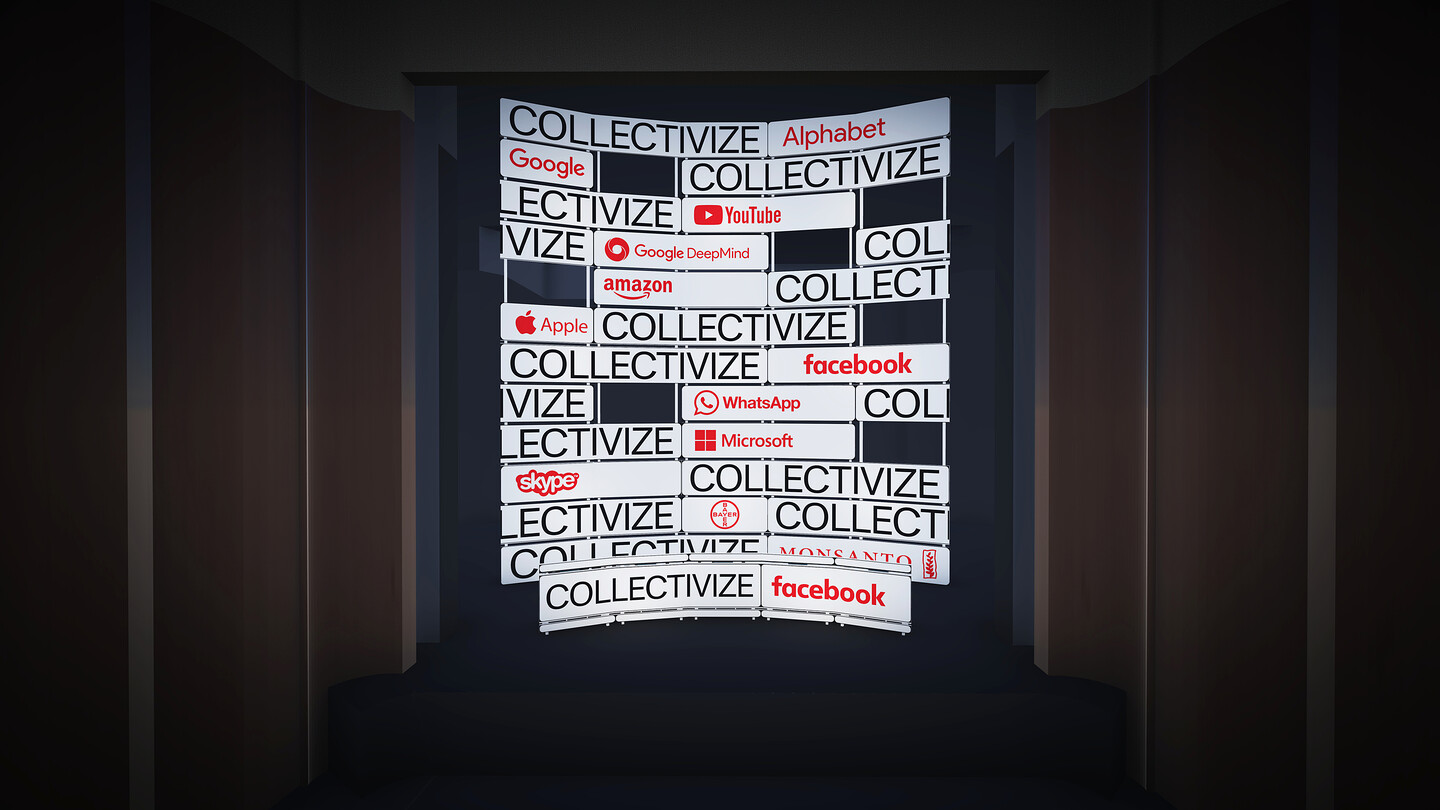

Jonas Staal Collectivizations

Decades of capitalist propaganda have reduced the notion of collectivization to Stalinist terror. This flattening of the term dismisses the breadth of forms that collectivization can take: from nationalizing communal resources and production, to other-than-human redistribution efforts to establish comradely ecologies. We need a more serious analysis of the different forms and outcomes of collectivization efforts in egalitarian movements around the world, from the deep past to recent history. The success of anti-collectivist propaganda also keeps us from revalidating collectivization’s present-day importance for regaining control over common resources in the face of massive extraction by trillion-dollar companies. It is therefore essential to explore the collectivized imaginaries and practices—collectivizations, in the plural—that make egalitarian forms of life imaginable and actionable.

1. Other Collectivizations

In capitalist propaganda, the notion of collectivization, its multiple meanings and forms of implementation, are trapped in a time capsule labelled “totalitarianism.” It is ridiculed and demonized by historians such as Oleg Khlevniuk, who decries Stalin’s 1929 proclamation for the construction of large-scale collective farms (kolkhozes) as the “brainchild of socialist fanatics.”1Other historians, less driven by anti-communism, such as Moshe Lewin, argue that while the brutal costs in lives and the use of state terror in the era of Stalinist collectivization are undeniable, “The whole set of repressive and terrorist measures has too often monopolized the attention of researchers, at the expense of the broader panorama of social changes and state building.”2 In this light, Lewin emphasizes that the very use of the term “collective” was inappropriate. He argues instead that the kolkhoz was “a hybrid structure containing incompatible principles … without ever becoming either a cooperative, a factory, or a private farm.”3 Such an approach turns the usual critique of Soviet collectivization on its head: rather than being all-encompassing, it might not have even been collective enough to be called collectivization.

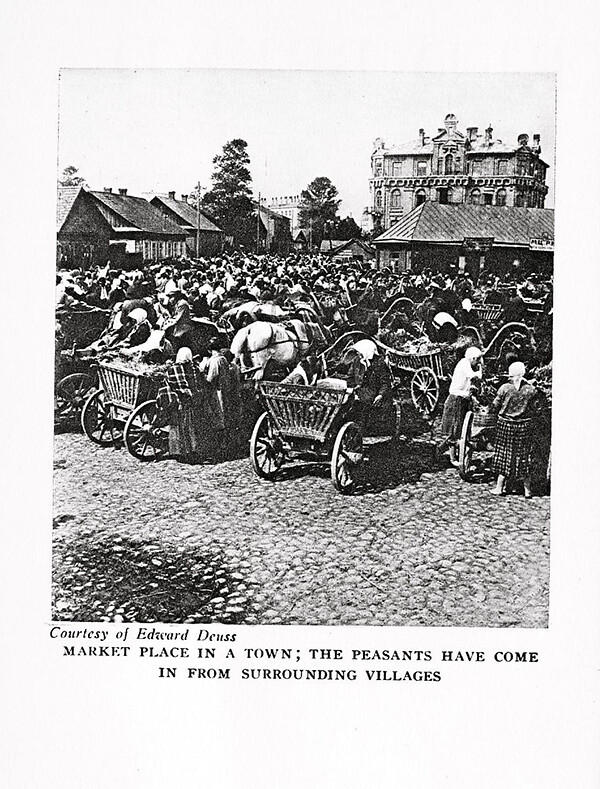

Early reports by writer Maurice Hindus on the creation of the kolkhozes are an important record for engaging with Lewin’s call for a “broader panorama” on collectivization. A Russian-American émigré, Hindus returned to his home village to describe the collectivization process, published in his 1931 book Red Bread. He observes the protests by the peasant population against the relentless liquidation of the kulaks (property-owning peasants), whose families, if lucky, faced the choice between exile or joining the kolkhoz. But he simultaneously witnesses the creation of free nurseries and cultural centers across the countryside, guaranteed maternity leave for kolkhoz members, the success of cooperative stores, emancipation from the firm grip of the Orthodox Church, and the liberation of women from marriage entrapment and subservience. Hindus is unscrupulous in speaking of “dictatorial Soviet standards,”4 but this does not keep him from seeing the Soviet Revolution as a “double-armed power” of both repression and mass emancipation.5 One does not redeem the other, nor does one legitimize the other, but they are equally real parts of its history.

It is a great historical loss that we have come to identify collectivization’s inherent relentlessness with state-imposed mass violence, due to Stalinist terror and enduring anti-communist propaganda. In recent decades, other terms such as “commoning” and the “commons” have been employed to recuperate the spirit of historical, emancipatory struggles against the primacy of private property. But as Silvia Federici writes, “Since at least the early 1990s, the language of the commons has been appropriated by the World Bank and the United Nations and put at the service of privatization.”6 In contrast to this neoliberal use of commoning language, a feminist theory of the commons, argues Federici, builds on “the collective experiences, the knowledge, and the struggles that women have accumulated concerning reproductive work, a history that has been an essential part of our resistance to capitalism.”7 Contrary to how those international organizations co-opt the term, Federici concludes that such a feminist theory of the commons entails the “collectivization of our everyday work of reproduction.”8

Federici’s use of the term “collectivization” distinguishes it from the capitalist capture of the commons, where commoning takes the form of World Bank microcredit policing and a demand for some form of preexisting property or physical ableness on the part of the commoner. Collectivization, however, is fundamentally indiscriminate: it completely rejects debt, and does not care whether people are “productive” bodies or not. Collectivization is relentless not because it is a priori violent, but because it includes and applies to everyone and everything.9

Just as Federici theorizes collectivization from a feminist perspective, there are many other historical and contemporary examples that resist the reduction of the term to Stalinist repression. The terrible famine of 1959–61 is adduced to discredit Chinese communes, but this entirely ignores—as Joshua Eisenman writes—the successes of the subsequent “green revolution” in China. Due to reforms of the nationwide agricultural research and extension system undertaken during the Cultural Revolution, experts rotating across communes pushed innovations and farming techniques. By the time of decollectivization in the early eighties, the communes had reached “historically high levels of agricultural productivity per unit land and per unit labor, life expectancy, basic literacy, and the promulgation of bookkeeping and vocational skills.”10 The communes were dismantled not because they were a failure, but because the reformist faction of Deng Xiaoping regarded them as too successful an inheritance of the Maoist era to keep in place.

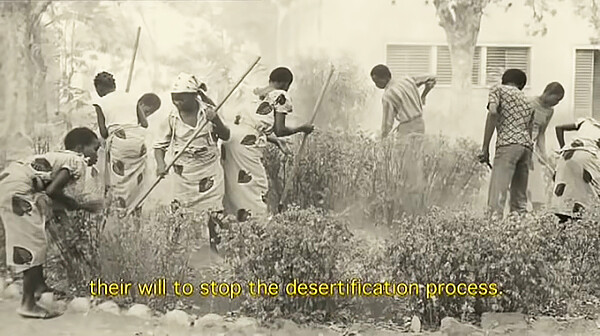

Thomas Sankara’s leadership of Burkina Faso (1983–87) embodies yet another take on the practice of collectivization, this time through an eco-socialist, anti-colonial, and anti-imperialist paradigm—another kind of “green revolution.” This manifested most famously in Sankara’s 1985 campaign to plant ten million trees, which aimed to turn reforestation and mass planting into a new “national and cultural tradition.”11 Here, collectivization cannot be reduced to the totalitarian cliché of state-imposed industrial farming, but manifests instead as an interdependent ecology of human and nonhuman workers: trees and humans struggle together for socialist self-determination. For Sankara, the campaign was a struggle against desertification, but also a struggle for resources that would sustain the country’s sovereignty from World Bank feudalism. In his words:

Our struggle for the trees and forests is first and foremost a democratic and popular struggle. Because a handful of forestry engineers and experts getting themselves all worked up in a sterile and costly manner will never accomplish anything! Nor can the worked-up consciences of a multitude of forums and institutions—sincere and praiseworthy though they may be—make the Sahel green again, when we lack the funds to drill wells for drinking water a hundred meters deep, while money abounds to drill oil wells three thousand meters deep!12

It is exactly this notion of self-determination that resonates with Coni Ledesma, representative of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP), when she speaks of the Bungkalan as a contemporary collectivization practice. In Filipino, Bungkalan means “to cultivate,” and relates to peasants and farmworkers who have been promised land reform, to no avail, and instead take collective repossession of idle lands on the islands of Negros, Mindanao, and Luzon, among others—despite continuing disappearances and murders perpetrated by the military. Rather than depending on massive state intervention, Ledesma describes how “farmers and sugar workers take their destiny and their lives in their own hands,” as a practice of collectivization in the here and now.13

With such examples in mind—from Federici to the Chinese communes and from Sankara’s eco-socialism to the Bungkalan—it would be better to speak of a history of collectivizations in the plural. As Vijay Prashad remarks, there needs to be a history of “polycentric communism” in thought that is not “centered around Moscow and Soviet foreign policy.”14 This helps to not only reconsider the pluralist histories of collectivizations in the past, but to also redefine collectivization struggles against the theft of common resources in the present and future.

2. Trillion-Dollar Dispossessions

Faced with the rise of trillion-dollar companies such as Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Bayer (Monsanto), with their massive extraction operations, there is an evident urgency to redefine the role of collectivization for egalitarian politics today, in order to reclaim control over political, economic, and social commons. When trying to grasp the vastness of the monopolization of resources by these companies, researchers draw parallels to the histories and presents of colonial empires. Siva Vaidhyanathan writes that “between Google and Facebook we have witnessed a global concentration of wealth and power not seen since the British and Dutch East India Companies ruled vast territories, millions of people, and the most valuable trade routes.”15Yanis Varoufakis claims that “the East India Company was no aberration” but should rather be considered the historical template that result in “mega-corporations like Amazon, Facebook, Google and ExxonMobil, which are effectively beyond the control of any nation-state.”16 Shoshana Zuboff argues that trillion-dollar companies are part of an era of “surveillance capitalism” and engage in neocolonial “digital dispossession,” with the result that “claims to self-determination have vanished from the maps of our own experience.”17

Zuboff’s reference to self-determination is relevant here if we want to understand the multiple forms of dispossession carried out by these trillion-dollar companies. As Karl Marx phrased it, the means of production are “the means of absorption of the labor of others,” meaning that “it is no longer the worker who employs the means of production, but the means of production which employs the worker.”18 This analysis seems fully applicable to Zuboff’s conception of surveillance capitalism, for in digital dispossession, data consumers also function as data workers.

Jodi Dean questions whether this form of surveillance capitalism is not better understood as a form of neofeudalism: “Cities and states relate to Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook, and Google/Alphabet as if these corporations were themselves sovereign states—negotiating with, trying to attract, and cooperating with them on their terms.”19 In Dean’s words, trillion-dollar companies are “doubly extractive,” because “platforms not only position themselves so that their use is basically necessary (like banks, credit cards, phones, and roads) but that their use generates data for their owners.”20 Facebook and Alphabet are less concerned with selling products to their users than with extracting behavioral data to sell to commercial and political advertisers, with the goal of eventually predicting future behavior in order to ensure guaranteed outcomes. While consuming, users are providing labor, just as that labor simultaneously becomes a form of consumption. In Blade Runner (1982), the bioengineered “replicant” Rachael perfectly summarizes the conditions for users of these platforms: “I’m not in the business. I am the business.”

When taking—consuming—a smart car for a spin, the driver is also operating as a data worker whose behavioral information is extracted to benefit restaurants and stores en route. The expanding internet of things uses our health monitoring apps to anticipate when we will become hungry, or our Google searches to predict when we will desire a new item of clothing. In the smart-city phantasmagoria, the world becomes a vast data mine that is excavated to predict our behavior, both as workers and consumers.21 This is what leads Vaidhyanathan to argue that if corporations such as Facebook merely recognized users as clients instead of resources, this alone could be considered revolutionary.22

Of course, it is important to emphasize that extraction through digital means remains a fundamentally material operation. This is exemplified by a recent lawsuit against Apple, Google, Dell, Microsoft, and Tesla based on field research conducted by antislavery economist Siddharth Kara, filed on behalf of families of children who were killed or injured at cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The primary phase of dispossession does not involve neofeudal data workers using their smartphones, laptops, and electric cars, but rather those who are forced to mine the materials to create these infrastructures and interfaces in the first place.23

This doesn’t mean, however, that people in the Global South are not also mined for data by trillion-dollar companies. Facebook piloted its “internet.org” project, later renamed “Free Basics,” under the guise of providing free internet to regions of the world that have limited access. The project was advertised as part of the company’s mission to “connect the world.” But the services were only free for limited apps, such as Facebook, and everything was hosted on Facebook’s servers. The goal, then, was to essentially replace the internet with Facebook.

This did not go without resistance: Indian net activists successfully fought Facebook for infringing on net-neutrality principles, leading to internet.org’s withdrawal from the country in 2016.24 But in many other countries, Facebook successfully contracted with governments to implement Free Basics, which in turn gave the company undue influence on national affairs. In the Philippines, where Free Basics went into effect in 2015, Facebook employees advised various candidates on their digital campaigns during the presidential elections of 2016. The winner, authoritarian Rodrigo Duterte, turned Facebook into his main media service, banning independent press from covering his inauguration.25 A year later, Facebook and the Duterte regime entered into a partnership to lay new underwater data cables, forging a profitable relation that ties Facebook indefinitely to Duterte’s murderous “war on drugs” campaign and his current push for an “anti-terror” bill to rid himself of any form of leftist opposition.26 Facebook might have been praised for its all-too-late suspension of Donald Trump’s account after his neofascist followers stormed the United States Capitol, but Trump’s incompetent authoritarianism is child’s play compared to Duterte’s Facebook-sponsored regime.

The emergence of neofeudalism—or “techno-feudalism” in the words of Varoufakis27—thus threatens self-determination in various ways: through multiple forms of dispossession, these companies extract our labor, equally as workers and as consumers; they dismantle any remaining notion of privacy; they structurally undermine democratic oversight and shared ownership; and they enable new forms of authoritarian (corporate) government. What twenty-first century collectivized imaginaries and collectivization practices might help us reclaim ownership over our common resources?

3. Collectivized Imaginaries

As we consider contemporary strategies for collectivizing resources and forms of technology, it is important to remember that users are the ones who initially funded these trillion-dollar companies—not just through unpaid data work as described above, but also through public investment, without which these companies could not have come into existence in the first place. Apple’s so-called “innovations” are inconceivable without US government–financed technological research.28Amazon could not have kickstarted its operations without the publicly funded postal system of the US and other countries, through which it continues to be subsidized;29 and as Andreas Petrossiants remarks, “Many of Amazon’s workers are so underpaid that they receive what little welfare benefits still exist in the US—meaning taxpayer money is essentially funding the social reproduction of Amazon workers.”30 Alphabet would not exist without the knowledge production of others, who provide its search engine’s content.31 Bayer would be of no value if it did not steal decades and centuries of seed knowledges and practices from farmers and Indigenous peoples.32 That users have collectively worked for these companies, paid for them, and been expropriated by them, without renumeration of any kind, frames the core argument for transferring them to collective ownership.

Such an endeavor is not without precedent. At certain critical moments in history, even liberal-democratic societies have recognized that private enterprise can disproportionately impact public well-being; in these moments, some companies and sectors have been placed under public control. During the 2008 financial crisis, a number of banks were (temporarily or partially) nationalized—Northern Rock in the United Kingdom, Bankia in Spain, ABN Amro in the Netherlands—when their criminal dealings in financial derivatives ruined the lives of precarious people all over the world. Spain temporarily nationalized private health care during the coronavirus pandemic.33 While these actions were taken primarily to rescue a disastrous economic system, they nonetheless display a recognition that banks and privatized health care threaten collective self-determination. The same recognition should be extended to trillion-dollar companies.

It is in this light that Wendy Liu argues for “more democratic control over the online platforms we spend so much time on, through user ownership, state ownership, stronger regulation, or decentralization.” Liu further emphasizes the need to “increas[e] worker mobility” through portable personal data, which could be moved from one platform to another in order to block further monopolization, and to deprive trillion-dollar companies of their “control over intellectual property.”34

Regaining democratic control over trillion-dollar companies also means repurposing them to serve the public good. Nationalization campaigner Paris Marx argues that the logistical urgencies of the coronavirus pandemic provide further rationale for placing Amazon under public ownership, by integrating it into the United States Postal Service (USPS):

The key task of a publicly owned Amazon in this moment of crisis would be to maintain the supply chain so it can continue delivering the necessities that people rely on, with priority given to those items. However, it should also begin preparing for the large-scale delivery of packages containing food staples and essential items to every home in the country, making use of the combined labor power of USPS and Amazon delivery workers, but also the infrastructure that only the USPS has: post offices all across the country, even in small rural communities that aren’t economical for private-package delivery companies to service.35

This is not the end of the nationalization effort Marx proposes. He also argues that Amazon’s web services, its infrastructure, and its data centers could become a “strong backbone” for a publicly owned internet. Whole Foods, an Amazon subsidiary, could be “reoriented to make a food hall that provides food to the community” and could also serve as a foundation for an expanded Meals on Wheels program. Amazon Studios could be reorganized to produce smaller, mid-budget indie and alternative films, which are currently marginalized to nonexistence due to the increased consolidation of large production studios that prioritize blockbuster output.36

Liu’s and Marx’s demands for democratic oversight and public ownership resonate with current workplace mobilization. The global campaign Make Amazon Pay, coordinated by Global UNI and Progressive International, was launched on “Black Friday” in 2020, demanding workplace improvements and job security for Amazon employees, a reversal of the company’s ban on unionization, a commitment from Amazon to achieve carbon neutrality, and full taxation of the retail giant.37 When the campaign was launched, tens of thousands of Amazon workers gathered in front of warehouses across the world, from Bangladesh to India, Australia to Brazil, the United States to the United Kingdom, Germany, and Poland.

The visual morphology of the campaign, which I developed together with Remco van Bladel in close dialogue with the organizers, aimed at two things. Firstly, the famous Amazon logo, which can be read as both a smile and a forward arrow, was doubled and placed on a red canvas to emphasize the demand to return: return rights to Amazon workers, return their hard work by providing benefits and financial security, return the environmental costs of excess carbon emissions, return the profits earned through tax avoidance. Secondly, hijacking and socializing Amazon’s visual identity was also intended as a first step toward the company’s replacement: our campaign symbols gestured towards a future Amazon owned and governed by its workers and users.

Creating a “visual portal” that points towards a future of workers’ ownership and self-governance is also central to the collective action lawsuit against Facebook that I initiated with human rights lawyer Jan Fermon, which we will file at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva. In line with Zuboff, we argue that the ownership model of Facebook and other trillion-dollar companies fundamentally infringes on the self-determination of peoples and individuals. As a consequence, we demand that the Council recognize Facebook as a public entity, and transfer ownership to its 2.8 billion users.

We are asking neither to reform nor nationalize Facebook: our approach to collectivization aims to turn the Facebook platform into a transnational cooperative, owned and governed by its users.

To replace the economy of extractivism and private ownership with a common, collectivized economy, cultural work is crucial. In Varoufakis’s political sci-fi book Another Now (2020), we encounter a parallel reality in which the 2008 financial crisis did not result in a consolidation of techno-feudalism; instead, it marked a fundamental turning point towards a “corpo-syndicalist” alternative. In this “another now,” a movement called Ossify Wall Street brings a new group into being: the Ossify Capitalism Rebels. Their actions target both physical spaces and the digital realms of techno-feudalism. Employing a “double strike” strategy, the OC Rebels help organize a strike among Facebook workers; at the same time, they convince masses of Facebook users not to log on, starving the company of valuable data.38 Other major “tech strikes” follow, forcing a halt to the extraction economy of Facebook and other trillion-dollar companies. Feeling the pressure, the political class passes a new Digital Rights Act that guarantees every person on earth full property rights over their own data:

Starved of their targeted advertising revenues and access to stock exchanges, the new shareholders of Google, Facebook and their ilk—employees owning one share each—were forced to seek the financial support of their community of users. In a surprisingly short time, what used to be the world’s greatest and greediest private monopolies had mutated into vast digital communes.39

Varoufakis shows the power of the cultural imaginary to recognize our current present as criminal, compared to the feasible pathways towards the digital communes of another now. It is in this light that we should see the work of the TESA Collective, which creates cooperative board games. It is hard to name a popular game, book, or film that does not involve a storyline based on a predatory win-or-lose dichotomy—and this shows how culturally embedded the extractive imaginary truly is. From Monopoly to Risk and Settlers of Catan, many board-game players are trained from an early age to understand narrative excitement through the theft of the commons: my gain is based on everyone else’s loss. The TESA Collective’s games, such as Co-Opoly, Rise-Up, and Strike, are instead based on collectively identifying shared oppressors—private capital and authoritarian governments. These games task players with creating large coalitions among workers, faith communities, students, alternative media outlets, and other groups, helping to train future social-movement organizers and cooperative members.40 We find real-life applications of such cooperative efforts in Clara Balaguer’s project Troll Palayan, which organizes meme-creation workshops, or what she calls “organic troll farms” (“palayan” means “rice paddy” in Filipino). The projects aims to reclaim the joys of collective memology to “dismantle toxicity in cyberspace.”41

In these examples—from Paris Marx’s mappings of nationalized trillion-dollar companies, to Varoufakis’s description of another now, to the training of cooperative mentalities by TESA Collective and Balaguer—collectivized imaginaries serve as the foundation for constructing collectivized realities.

4. Ninety-Four Million Years of Collectivism

Capitalism—along with its neo- and techno-feudal mutations—is maintained in part by a certain origin myth. Unjust systems of predation are portrayed as an inherent part of the “circle of life” or “human nature.” Through this narrative, collectivization is framed as a rarity in history, as a utopian glitch that may be desirable but is in fact incompatible with human reality. Collectivization might look good on paper, but not in practice. In this line of thought, capitalism is naturalized: it is not what we want, it’s simply what we are.

Nick Estes challenges this origin story by arguing that “Indigenous ways of relating to human and other-than-human life exist in opposition to capitalism, which transforms both humans and nonhumans into labor and commodities to be bought and sold.”42 Furthering this argument, the Red Nation coalition—of which Estes is a member—demands “dignified lives as Native peoples who are free to perform our purpose as stewards of life if we are to protect and respect our nonhuman relatives—the land, the water, the air, the plants, and the animals.”43 Through this emphasis on comradely relationality within ecosystems, the notion of private property—of legalized theft—is rejected. The struggle for collectivization today, then, is no novelty, because collectivized practices preceded capitalism all over the planet. In their proposition for a “Red Natural History,” Not An Alternative refers to this as a “world in common,” existing as a horizon within our world of capitalist capture.44

Capitalism’s origin myth even reaches further back than humans have existed on earth. For a long time, geologists claimed that the carnivorous “Cambrian Explosion” that occurred 541 million years ago was the evolutionary leap that resulted in complex life on earth. But for decades geologists ignored facts that contradicted this view—which might have something to do with their inability to imagine that complex life could result from anything other than capitalist predation.

However, in the geological era immediately preceding the predatory Cambrian Period—known as the “Ediacaran Period”—complex life-forms coexisted in a cooperative, nonpredatory oceanic world. The Ediacaran Period lasted from 635 to 541 million years ago—ninety-four million years of collectivism. In is in this light that geologist Mark McMenamin asks, “Do socialism and capitalism have, fundamentally, an ecological basis?”—implying that the Ediacaran could be considered a period of pre-socialist socialism, and the Cambrian as a period of pre-capitalist capitalism.45Ediacaran biota resemble disks, worm-like shapes, and elegant plant-like forms characterized by a quilted body architecture. They are regarded as neither plants nor animals, their existence defying biological and gendered classification. Their collectivized ecology operated through photosymbiosis, chemosymbiosis, and osmotrophy, recirculating nutrients amongst one another, making predation unnecessary.46

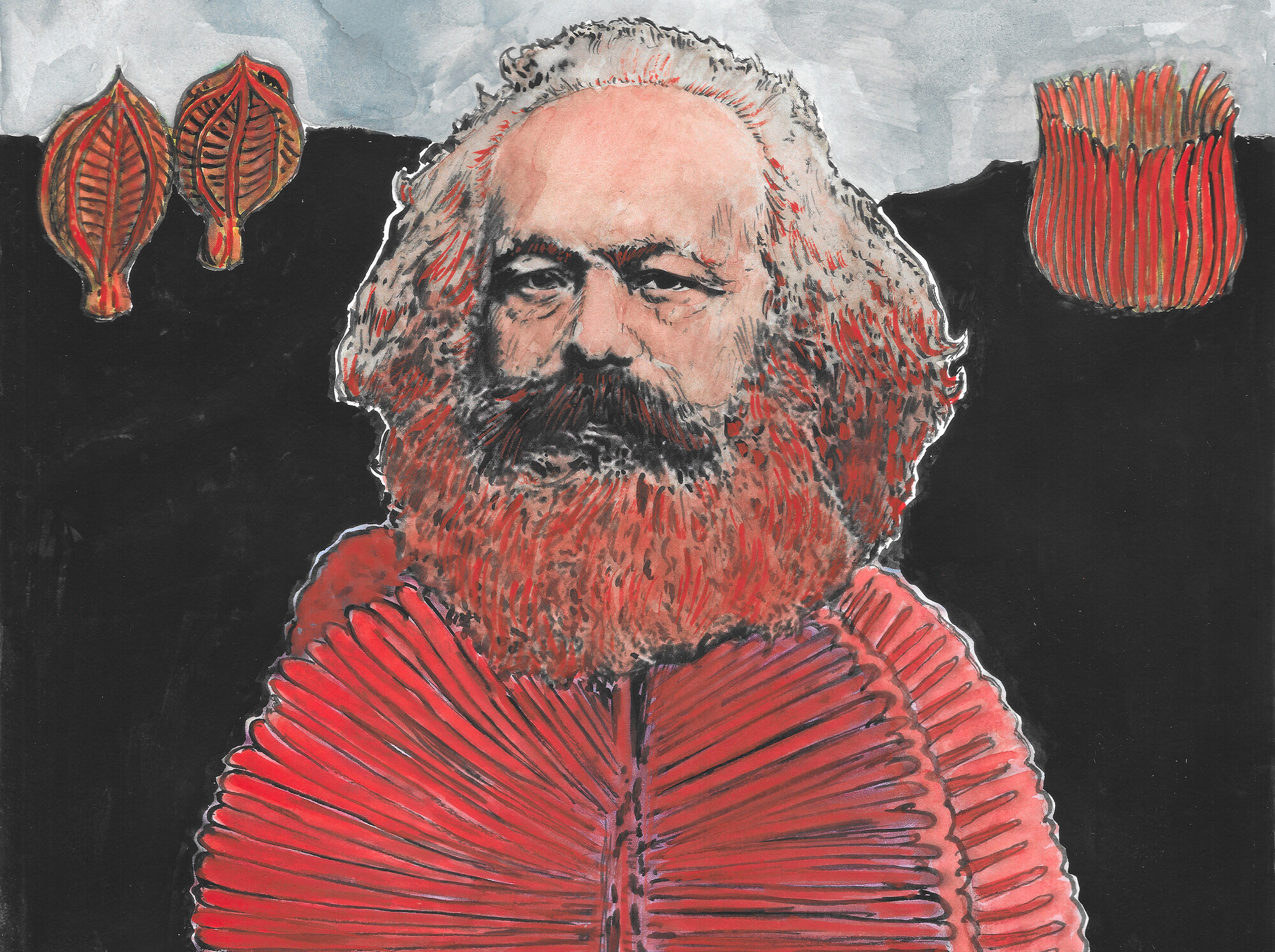

The Ediacaran is named after the Ediacaran Hills in South Australia, home of the Adnyamathanha people. We might thus evoke here the Aboriginal concept and practice of The Dreaming, where ancestors and descendants coexist.47 Do Ediacaran biota, such as Charnia, Rangea, Kimberella, Swartpuntia, Spriggina, and Ernietta, coexist in a dream space with Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, Alexandra Kollontai, Rosa Luxemburg, Hồ Chí Minh, Célia Sanchez, and Thomas Sankara? Do they share the same dream, or dream of one another, beyond time and across space? A dream of socialized ecologies of coexistence, a dream of perpetual redistribution and collectivization of life? These questions belong to the field of “Proletgeology”: earth-memory studies of other-than-human proletarian and collectivist life-forms.48

While we should not naturalize the ninety-four-million-year Ediacaran Period as a pre-socialist socialism the way the ruling classes naturalize capitalism, it is essential to recognize that human and other-than-human work towards collectivization is as much a part of our deep history as of our struggles in the present. Our challenge today is to solidarize these dreams and imaginaries to collectivize worlds for all.

I want to thank Adwait Singh, iLiana Fokianaki, and Andreas Petrossiants for their editorial support in writing this essay. I further want to thank Singh and Mihnea Mircan for our ongoing conversations about Ediacaran collectivism, and Proletgeologist Vincent W. J. van Gerven Oei for his counsel. Part of the research for this essay emerged from the “Collectivizations”interview series that I co-programmed with Marina Otero Verzier and Flora van Gaalen for Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam.

Jonas Staal is a visual artist whose work deals with the relation between art, propaganda, and democracy. His most recent book is Propaganda Art in the 21st Century (MIT Press, 2019). © 2021 e-flux and the author

Source: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/118/394239/collectivizations/

GO BACK